Hans Hofmann was one of the twentieth century’s most influential teachers and one of its most inspired artists. Originally from Germany, Hofmann immigrated to America in the 1930s and became a citizen of the United States. By the time he came to New York he had not only had direct experience with avant-garde Parisian artists such as Henri Matisse and contemporary movements including Fauvism and Cubism, but also had an understanding of the ideologies of Wassily Kandinsky. Because of his knowledge of European modernism, he became a beacon for aspiring young artists in America. He was among the first to incorporate the ideas of modernism into a system of teaching; his methods influenced several generations of painters.

Hans Hofmann was one of the twentieth century’s most influential teachers and one of its most inspired artists. Originally from Germany, Hofmann immigrated to America in the 1930s and became a citizen of the United States. By the time he came to New York he had not only had direct experience with avant-garde Parisian artists such as Henri Matisse and contemporary movements including Fauvism and Cubism, but also had an understanding of the ideologies of Wassily Kandinsky. Because of his knowledge of European modernism, he became a beacon for aspiring young artists in America. He was among the first to incorporate the ideas of modernism into a system of teaching; his methods influenced several generations of painters.

Hofmann, born March 21, 1880, in Weissenburg, was raised in Germany. In 1886, the family moved to Munich where Hofmann’s father was employed by the government. At school, the young Hofmann excelled in mathematics, sciences, and music and learned to play the violin, piano, and organ. He also began to draw. At the age of sixteen, and with his father’s assistance, Hofmann was made assistant to the director of Public Works of the State of Bavaria. His keen mathematical skills led to several scientific inventions; science, however, was not his passion.

With a growing interest in art, Hofmann began to pursue formal training in the subject. In 1898, he enrolled in Moritz Heymann’s school of art in Munich. He studied with Impressionist painter Willi Schwartz and befriended fellow students such as Jules Pascin. Through Schwartz, Hofmann made the acquaintance of a Berlin collector Philipp Freudenberg in 1903. With Freudenberg’s support, Hofmann moved to Paris around 1904 and remained there almost permanently until 1914. Maria (Miz) Wolfegg, whom he met in Munich in 1900 and whom he would eventually marry in 1924, joined him in Paris around 1904.

Hofmann took full advantage of all the opportunities the city had to offer an aspiring artist. He attended night classes at the Ecole de la Grande Chaumière and courses at the Académie Colarossi. While in Paris, he also came to know the leading lights of the vanguard art movements including Matisse, Picasso, Braque, and Robert and Sonia Delaunay--he became particularly close with the Delaunays. His style of painting from this period was heavily influenced by Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism. During these years he began to exhibit his work regularly, particularly in Germany. In 1908 and 1909, he exhibited with the New Succession in Berlin, and in 1910 had his first show at Paul Cassirer Gallery, also in Berlin. Hofmann and Wolfegg’s lives, like so many others, were changed dramatically by World War I. In 1914, the couple went to Corsica for Hofmann’s health (he suffered from tuberculosis), but were soon called to Germany because of illness in his family. While en route to their homeland, the war broke and they could not return to France. During this time Hofmann discovered Wassily Kandinsky’s On the Spiritual in Art and was immediately struck by its philosophy. He also came to know Gabriele Münter, who was a friend of Wolfegg’s. She asked him to store some of the works Kandinsky had left behind when he fled to Russia and, in return for this favor, offered him one of the artist’s watercolors. Hofmann kept this picture his entire life.

Once confined to Germany, Hofmann discovered that he could not serve in the army because of his lung problems, so he decided to teach. In the spring of 1915, he opened the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts in Munich and thereafter teaching became his main focus for the next several decades. Hofmann stated his philosophy of art in the prospectus for his Munich school, “Art does not consist in the objectivized imitation of reality. Without the creative impulse of the artist, even the most perfect imitation of reality is a lifeless form . . . form receives its impulse from nature, but is nevertheless not bound to objective reality; rather, it depends to a much greater extent on the artistic experience evoked by objective reality and the artist’s command of the spiritual means of fine art, through which this artistic experience is transformed into reality in painting."(1) These ideals did not change drastically over the years, but the means by which he achieved them did. Among the students who studied with Hofmann after World War I ended were Worth Ryder, Louise Nevelson, Vaclav Vytlacil, Carl Holty, Alfred Jensen, and Ludwig Sander. He held summer classes throughout the 1920s in Bavaria, Ragusa, Capri, and St. Tropez. He also made frequent visits to Paris. Hofmann’s demanding schedule left him little free time to paint during these years, but he drew incessantly.

The 1930s were a time of tremendous travel for Hofmann and a period of growing appreciation for his art. In 1930, he was invited by his former pupil Worth Ryder to teach a summer session at the University of California, Berkeley. Ryder was chairperson of the Department of Art at Berkeley. The following year he taught at Berkeley again, and also gave classes at the Chouinard School of Art in Los Angeles. Also in 1931, Hofmann exhibited a series of drawings at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco; this was his first showing in America. In 1932, Hofmann was asked to instruct at Chouinard again during the summer months; however, because of growing political concerns at home, he did not return to Germany at the end of the sessions, but settled instead in New York and never returned permanently to his homeland. His former student Vytlacil helped him obtain position at the Art Students League. Hofmann tried to keep his own school in Germany open during these years, but in the fall of 1933 classes ceased, and by 1936 the school was closed. In 1939, his wife was able to flee Europe and joined him in America.

While his European school may have folded, Hofmann was determined to keep teaching. In the summers of 1933 and 1934, he was one of the guest instructors at the Thurn School of Art in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Though these kinds of assignments were surely enjoyable, Hofmann wanted his own school, and in the fall of 1933 he established the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts in New York. This undertaking had more than one location during its lifetime; it opened at 444 Madison Avenue, moved to 137 East 57th Street in 1936, to 52 West 9th Street in 1936, and to 52 West 8th Street in 1938. Hofmann also found a summer school in Provincetown, Massachusetts in 1935. Among his many students were Lee Krasner, Helen Frankenthaler, Burgoyne Miller, Charles and Ray Eames, Red Grooms, Joan Mitchell, and Larry Rivers. Through a series of lectures given in the winter of 1938-1939, Hofmann also came to know Arshile Gorky and the critic Clement Greenberg. By means of his tireless and tremendous teaching efforts Hofmann influenced and inspired generations of artists. His own paintings from this period show the continued influence of early European modernism, especially the ideologies of Matisse.

In the 1940s, Hofmann began to achieve recognition for his painting and became an integral part of the vanguard American art scene. In 1941, soon after he became an American citizen, he had a one-person show at the Isaac Delgado Museum of Art in New Orleans. The following year Lee Krasner introduced Hofmann to Jackson Pollock. In the early and mid forties, Hofmann and Pollock both experimented with dripping their paint onto their canvases. Around 1944, Pollock introduced Hofmann to Peggy Guggenheim who arranged his first solo show in New York at her Art of This Century Gallery. During the forties Hofmann’s approach to painting began to change and his imagery became much more abstract, though identifiable subject matter still appeared in his pictures from this period.

Throughout the 1940s, Hofmann exhibited regularly in group and one-person shows. Among the venues that included his works were the Arts Club of Chicago, the Milwaukee Institute of Arts, the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, and 67 Gallery, Mortimer Brandt Gallery, and Betty Parsons Gallery, all in New York. Paintings by him were also seen in galleries and museums in Pittsburgh, Denton, Texas, Norman, Oklahoma, and Memphis, Tennessee. Beginning in 1947, Hofmann was represented by the Kootz Gallery in Manhattan and had a solo show there almost every year until his death. Toward the end of the 1940s, Hofmann was honored with a retrospective exhibition at the Addison Gallery of American Art at The Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. In addition, the Parisian Galerie Maeght held a major exhibition of Hofmann’s work in 1949. Hofmann renewed his friendships with Picasso and Braque when he visited France for this show.

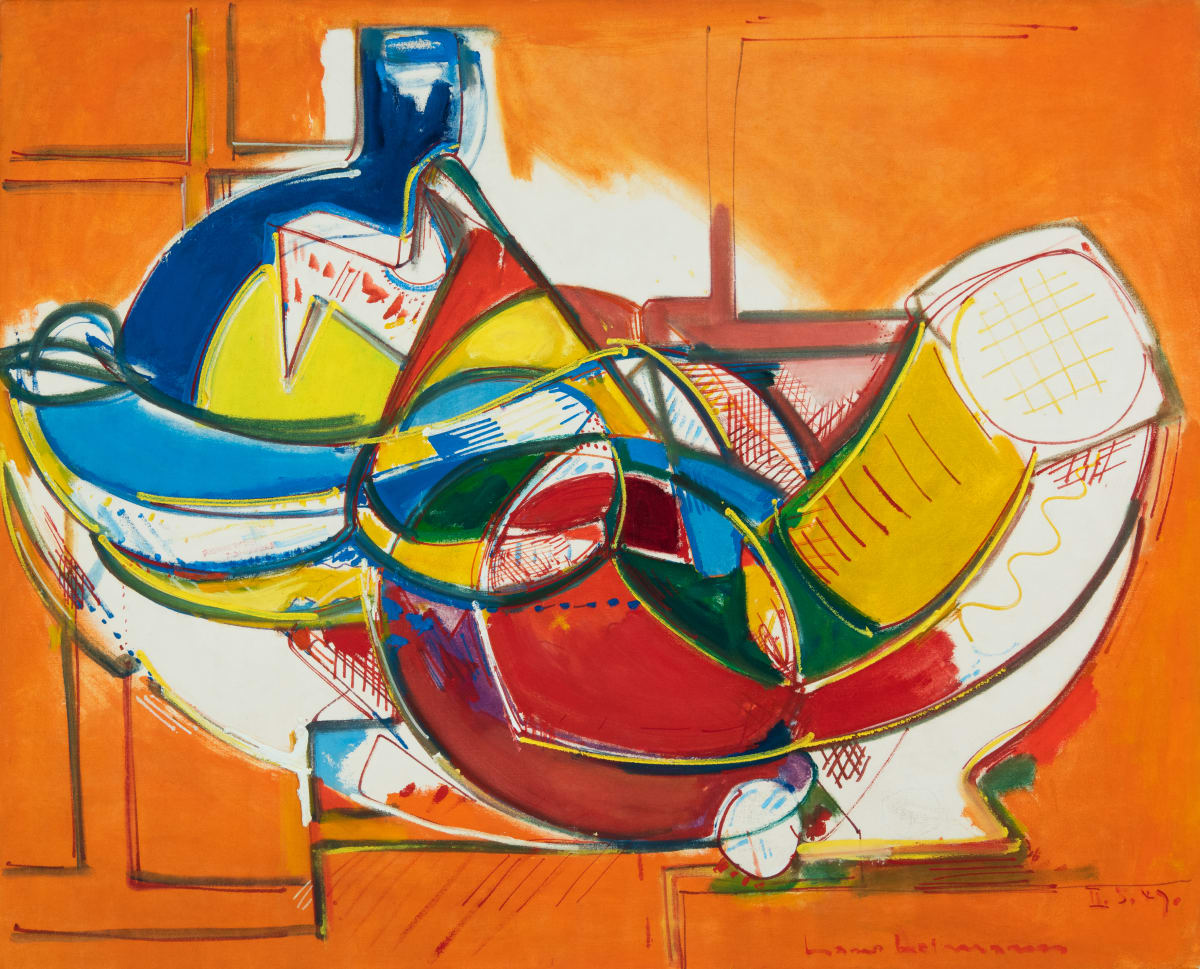

In the final decades of his life, Hofmann was much more prolific as an artist. He also remained at the center of activity amongst the group of artists referred to as the Abstract Expressionists. He participated in many solo and group exhibitions, including the XXX Venice Biennale. In the 1950s and 1960s, several retrospectives of his work were held at institutions such as the Art Alliance of Philadelphia, the Whitney Museum of American Art (which traveled to Des Moines, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Utica, and Baltimore), the Fränkischen Galerie in Nuremberg (which traveled to Cologne and Berlin), and the Museum of Modern Art. The MoMA show was sent to venues across America as well as in South America and Europe.

In 1958, Hofmann gave up his forty-odd-year teaching career and devoted himself to painting full time. He moved his studio into the buildings once occupied by his New York and Provincetown art schools. In his late works Hofmann abandoned almost all reference to recognizable imagery and dedicated himself to the explorations of color, space, and form in his pictures. His style alternated between the highly energized and gestured drip paintings and the quieter, heavily paint-laden, and constructed rectangles. In addition, Hofmann suggested meaning and relationships in his paintings through evocative and descriptive titles.

During the final years of his life Hans Hofmann received many accolades. He was awarded an honorary membership in the Akademie der Bildenden Kunste in Nuremberg. He was also given honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degrees from Dartmouth College, the University of California, Berkeley, and the Pratt Institute, New York. In addition, he received the Solomon Guggenheim International Award. Also, he was made a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters.

The 1960s were a time of yet more change in Hofmann’s life, personally and professionally. In 1963, Maria (Miz) Hofmann died. The same year Hofmann donated forty-five of his paintings to the University of California, Berkeley and agreed to help fund the construction of a permanent space to display his work in the new university museum. In 1964, he met Renate Schmitz, his junior by nearly fifty years, who was the inspiration for the Renate Series of paintings executed by Hofmann in 1965. In that year, and four month before Hofmann’s death, the two married.

Hans Hofmann died in New York, February 17, 1966.

References:

Yohe, James, ed. Hans Hofmann, with essays by Hans Hofmann, Sam Hunter, Frank Stella, and Tina Dickey. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2002.

Dickey, Tina and Friedel, Helmut. Hans Hofmann. Munich: Lenbachhaus, 1997; New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1998.

Goodman, Cynthia. Hans Hofmann. Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1990.

Bannard, Walter Darby. Hans Hofmann: A Retrospective Exhibition. Houston: The Museum of Fine Arts, 1976.

Hunter, Sam. Hans Hofmann. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1963.

Notes:

1) Helmut Friedel, “To sense the invisible and to be able to create it--that is art,” in Hans Hofmann (Munich: Lenbachhaus, 1997; New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1998), 9.