Central to the development of Dada and Surrealism in the United States, Man Ray was the sole American artist to claim such a prominent role in both artistic movements.

Central to the development of Dada and Surrealism in the United States, Man Ray was the sole American artist to claim such a prominent role in both artistic movements. Producing paintings, photographs, collages, sculptures, and even avant-garde films, he consciously avoided easy classification, refusing to be recognized solely for his efforts in any one medium. Although this desire to resist stereotyping at first frustrated some scholars and critics, it is Man Ray’s dedication to innovation that now defines his artistic legacy.

Central to the development of Dada and Surrealism in the United States, Man Ray was the sole American artist to claim such a prominent role in both artistic movements. Producing paintings, photographs, collages, sculptures, and even avant-garde films, he consciously avoided easy classification, refusing to be recognized solely for his efforts in any one medium. Although this desire to resist stereotyping at first frustrated some scholars and critics, it is Man Ray’s dedication to innovation that now defines his artistic legacy.

Showing a propensity for drawing and painting at an early age, and involving himself in artistic circles throughout his life, Man Ray adopted his pseudonym in 1909. Born Emmanuel Radnitzky, he was raised in Philadelphia by his Russian Jewish parents, who had only recently immigrated to the United States. He worked as an engraver and illustrator after graduating from high school in Brooklyn. From 1910 to 1912, he took life drawing classes supervised by Robert Henri and George Bellows at the Francisco Ferrer Social Center. The following year he moved to Ridgefield, New Jersey, the site of an informal artists’ colony. There he designed, illustrated and produced several small press pamphlets, such as the Ridgefield Gazook, published in 1915, and A Book of Divers Writings [sic].

A frequent visitor to Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery, Man Ray assimilated into his early work aspects of the European modernist art on view there. In the mid-1910s he introduced Cubist elements in his abstracted still lifes and landscapes, drawing on the geometric forms, compressed space, faceted planes of Analytic Cubism. In 1916 Man Ray met the poet and collector Walter Arensberg, and soon became a habitué of his salon, which included Marcel Duchamp and Jean Picabia, with whom Man Ray would collaborate on Rongwrong, an avant-garde journal. Together, Duchamp and Man Ray were the proponents of the short-lived New York Dada movement, central in calling into question the status of the object with “readymade” sculptures and promoting an irreverent, iconoclastic attitude. With Duchamp and patron Katherine Dreier, he was also a founder-member of the Société Anonyme, “a public, non-commercial center for the study and promotion of modern art.” (1)

After being exposed to the work of the European avant-garde on view in New York, Man Ray decided to travel to Paris, a trip funded by the sale of several paintings to the industrialist Ferdinand Howald. He remained in Paris for twenty years, until the onset of World War II forced him to flee. In 1922 he developed the “rayograph,” a method of producing images directly from objects on photo-sensitive paper similar to a photogram. Created by arranging recognizable objects in an apparently casual and arbitrary way, Man Ray’s rayographs transformed ordinary objects into mysterious images—a sensibility appreciated by the artist’s colleagues in Paris, who would collectively be known as Surrealists.

At first recognized as a portrait photographer, Man Ray captured his friends—such vanguard luminaries as Pablo Picasso, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, Georges Braque, James Joyce, and Jean Vanguard—and exhibited these works in at the opening of the café Boeuf sur le Toit. By 1923, Man Ray notes, “I was an established photographer.” (2) Commercial success followed, and Man Ray became one of the foremost haute-couture fashion photographers, publishing in Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar; his impulse was to “combine art and fashion,” collapsing the boundaries between the two domains. (3) Yet the artist maintained his experimental, avant-garde roots, publishing a scandalous collection of pornographic photographs in 1929 and exhibiting as a member of the Surrealists in several shows in the 1930s, such as those at Julien Levy gallery in New York, the New Burlington Gallery, London, the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, and the major group exhibitions Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Exposition Internationale de Surréalisme at the Galerie des Beaux-Arts, Paris, and Surrealist Paintings, Drawings, Objects at the London Gallery.

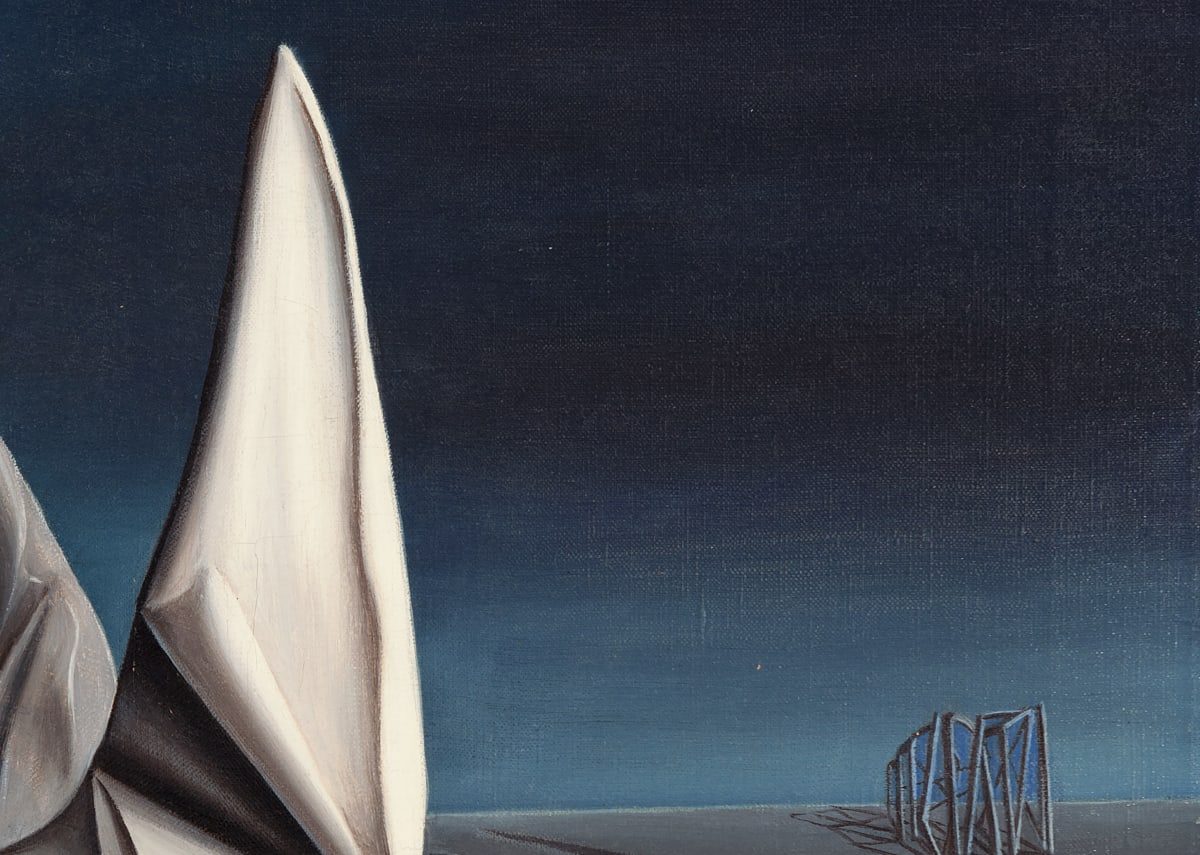

In addition to his participation in major group shows, during the 1920s and 1930s Man Ray also solidified his international reputation with numerous one-man exhibitions in the United States and in Europe. During this period Man Ray also continued to innovate, experimenting with the Sabattier, a solarization process that produced eerie photographic effects. By partially exposing his negatives to light, the artist created fantastic, dream-like images, ones that appeared to fuse the imaginary and the real. He used this solarization technique to great effect in his photographs of the female nude, producing poetic and mystical images of the nude that inspired his friends, artists Maurice Tabard and Raoul Tabac.

Beginning with the release of his first movie in 1923, Return to Reason, Man Ray also made substantial contributions to avant-garde film. He produced the first camera-less sequences of photographic images—“cine-rayographs”—developed by animating his rayographs. Throughout the 1920s he created such celebrated Surrealist films as Emak Bakia (1926), L’Etoile de mer (1928) and Les Mystères du Château de Dé (1929), forming with his colleagues Hans Richter, Luis Bunuel, and Salvador Dali a new cinematic genre.

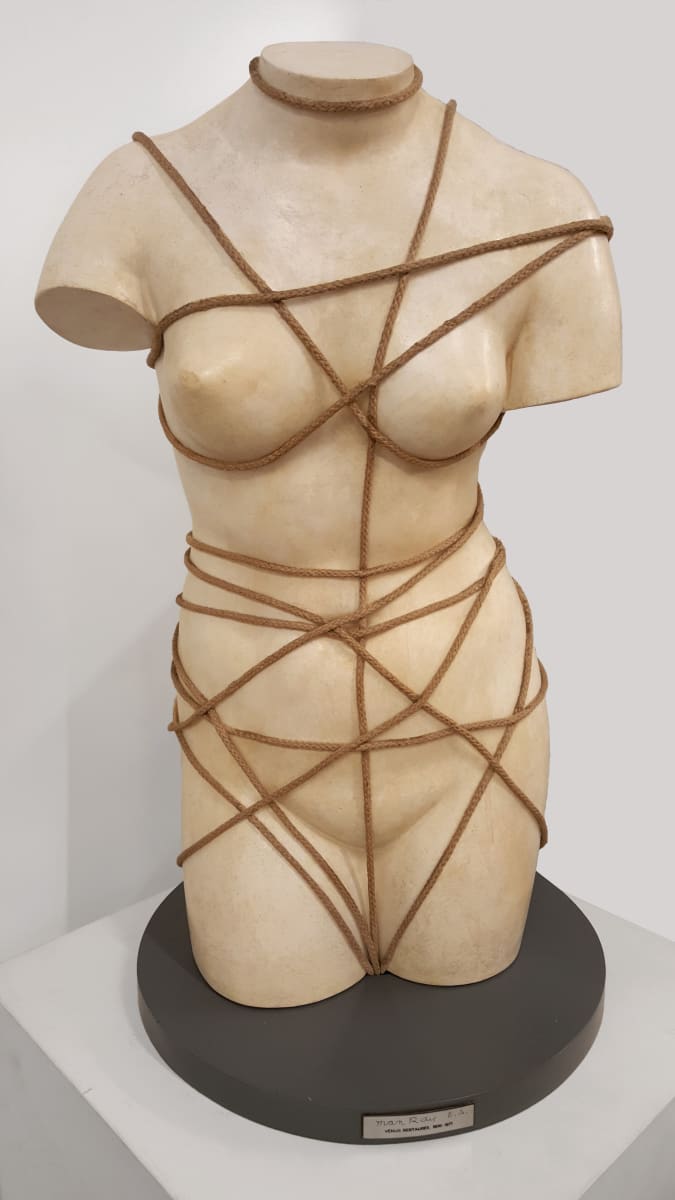

Man Ray settled in Hollywood in 1941, where he turned his attention primarily to painting and producing objects for ten years, when he returned to Paris. In 1961 Man Ray was awarded the gold medal in photography at the Venice Biennale, and in 1966 the Los Angeles County Museum of Art organized the first comprehensive retrospective of his work in the United States. Subsequently, a series of major retrospectives toured Europe, traveling to Milan, Rotterdam, Denmark, and the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris. Man Ray died in Paris on November 18, 1976.

1. Marina Vanci-Perahim, ed., Man Ray (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 8.

2. Man Ray, 1890-1976 (Ghent, Ludion Press, distributed by Harry N. Abrams, 1995), 318.

3. Vanci-Perahim, ed., Man Ray, 53.