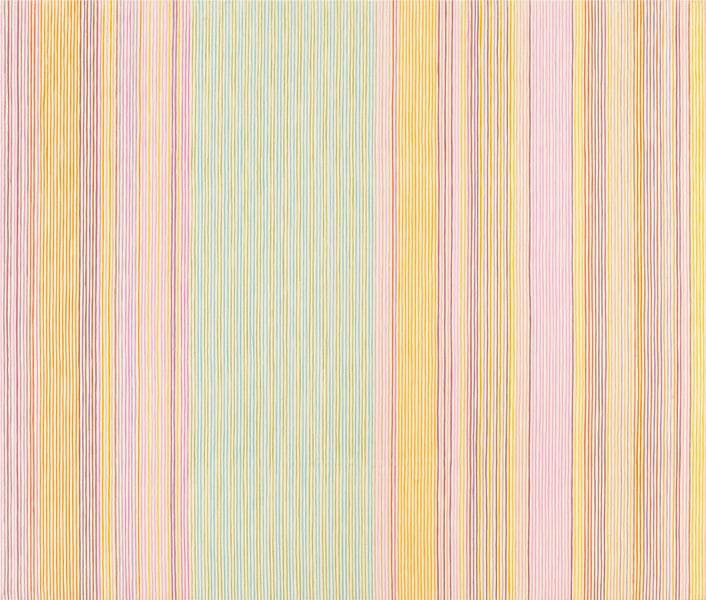

Gene Davis is best known for his "stripe paintings."

One of the three principles of the “Washington Color Painters,” Gene Davis is best known for his “stripe paintings.” Spending most of his life in the Washington metropolitan area, he was known early on as a sportswriter and later as a White House correspondent during the Franklin D. Roosevelt and Truman administrations, before becoming one of the city’s most influential and important artists and art instructors. In the mid 1960s, the city’s native son graduated from local icon to national phenomenon, as his particular breed of Color Field painting became identified with the aesthetic of the “Washington Color” school. This style of painting, which employed stripes, stains, and fields of color was as also practiced by his colleagues Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland.

One of the three principles of the “Washington Color Painters,” Gene Davis is best known for his “stripe paintings.” Spending most of his life in the Washington metropolitan area, he was known early on as a sportswriter and later as a White House correspondent during the Franklin D. Roosevelt and Truman administrations, before becoming one of the city’s most influential and important artists and art instructors. In the mid 1960s, the city’s native son graduated from local icon to national phenomenon, as his particular breed of Color Field painting became identified with the aesthetic of the “Washington Color” school. This style of painting, which employed stripes, stains, and fields of color was as also practiced by his colleagues Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland.

Although he did not attend art school, Davis frequented the Phillips Collection and the Washington Workshop for the Arts, and acknowledged Paul Klee, Jasper Johns, and Barnett Newman as “three dominant influences” on his own artistic development. (1) Davis often repeated the Swiss modernist’s characterization of doodling as “taking a walk with a line,” and he, like Klee, employed linear elements as a means of structuring ethereal and whimsical compositions. (42 The Washington painter admired in Johns’ work his use of everyday subjects, and his rejection of gestural paint handling in favor of harder-edged imagery.

After seeing Barnett Newman’s first solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1950, Davis developed an appreciation for the artist’s “little stripe blips on colored fields.” (3) The artist even acknowledged how a misinterpretation of Newman’s art launched his own style:

“When I first discovered Newman’s painting in the early 1950s, I was attracted to the vertical stripes and not the color fields, which are actually what his work is all about. You might say that, in borrowing the vertical stripe from Newman, I was taking only what I needed.” (4)

Almost thirty years later, in an overt nod to Newman’s Stations of the Cross from 1958, Davis created series of sixteen canvases, all in shades of gray, which he titled Tuxedo: Homage to Newman (1979).

Because of his nontraditional artistic background, in the 1950s Davis felt free to explore different media and surfaces of support, painting on irregularly shaped masonite, suspending gravel and rocks in oil paint, incorporating mirrors into his composition, and using pages of the phone book as the ground for his painterly explorations. It was in 1958 that Davis originated his all-over stripe painting, a motif that the artist would continue to explore for most of his career. His vertical stripes in the 1960s varied, from wide bands of candy-colored hues to thin lines clustered on the left and right side of the canvas, flanking a blank center.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, Davis began to receive regular invitations to participate in gallery group shows and also solo exhibitions. He received several one-man shows at the Corcoran Gallery of Art (1963, 1970, 1977), Jefferson Place Gallery in Washington, D.C. (1959-1962, annually), and the New York establishments Poindexter Gallery (1963, 1965-1967), and Fischbach Gallery (1967, 1968, 1970, 1971, 1973, 1976, 1977). He also participated in landmark group exhibitions, such as Clement Greenberg’s ground-breaking “Post Painterly Abstraction” (1964; originated at Los Angeles County Museum of Art), and “The Structure of Color” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The 1965 traveling exhibition, “Washington Color Painters,” which originated at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art finally gave a name to the particular breed of abstraction practiced by several of the area’s most notable artists.

In 1966 Davis began teaching at the Corcoran School of Art, an appointment which pushed him to continue to innovate and develop, as he claimed he learned as much from his students as they learned from him. He elaborated, “When you get kids who are willing to try anything, it makes you look at yourself again.” (5) Staying true to this motivation, the artist continuously experimented, even within his stripe format. In 1967, he went against the contemporary preference for large-format paintings, turning instead to miniaturized explorations. These “micro-paintings,” often less than a square inch in size, were radical in their incorporation of “small-scale color accents in large gallery spaces.” (6)

Between 1972 and 1982, he undertook a number of in situ projects, adapting his characteristic lines to specific locales: his stripes took form on the street in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in the front windows of the Willard Hotel in downtown Washington, on the walls of the Corcoran Gallery Rotunda, on the ground of the parking lot at Artpark in Lewiston, New York, and even became colored tubes of water for the Muscarelle Museum of Art in Williamsburg, Virginia. In 1970 the artist also experimented with video art.

A keen draughtsman, the artist occasionally incorporated drawings into his paintings, as well as other collage elements, such as popular imagery. Davis began working in this mode in 1958, largely abandoning it in the ensuing decades to concentrate on painting, only to return to it in the 1980s in suites of works known as “Symbols” and “Profiles.” In his “Symbols” series, he included visual fragments from mass-media newspapers and magazines.

Characteristic of the “Profiles” are silhouetted busts, in large and small dimensions, some rendered in stripes, others drawn in a child-like, whimsical hand. In 1983 Davis work was exhibited alongside children’s artwork in the traveling exhibition, “Child and Man: A Collaboration.” In 1985 Davis died of a heart attack in Washington, D.C.

1. Steven Naifeh, Gene Davis (New York: The Arts Publisher, 1982), 40.

2. Donald Kuspit, “A Perfect Music: Gene Davis’s Stripes,” in Jacquelyn Days Serwer, Gene Davis: A Memorial Exhibition (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987), 39.

3. Naifeh, Gene Davis, 40.

4. Ibid.

5. Charles C. Eldredge, “Foreword,” in Gene Davis: A Memorial Exhibition, 10.

6. Naifeh, Gene Davis, 125.