Kusama boldly pursued her obsessive personal vision, creating a body of work in which she both affirmed and obscured her own existence.

A “magnificent outsider” who “played a crucial, pioneering role at a time when vital changes and innovations were taking place in the field of art,” Yayoi Kusama has only recently enjoyed the critical attention and appreciation she has long deserved. (1) During almost two decades in New York, from 1958 to 1975, Kusama boldly pursued her obsessive personal vision, creating a body of work in which she both affirmed and obscured her own existence.

A “magnificent outsider” who “played a crucial, pioneering role at a time when vital changes and innovations were taking place in the field of art,” Yayoi Kusama has only recently enjoyed the critical attention and appreciation she has long deserved. (1) During almost two decades in New York, from 1958 to 1975, Kusama boldly pursued her obsessive personal vision, creating a body of work in which she both affirmed and obscured her own existence.

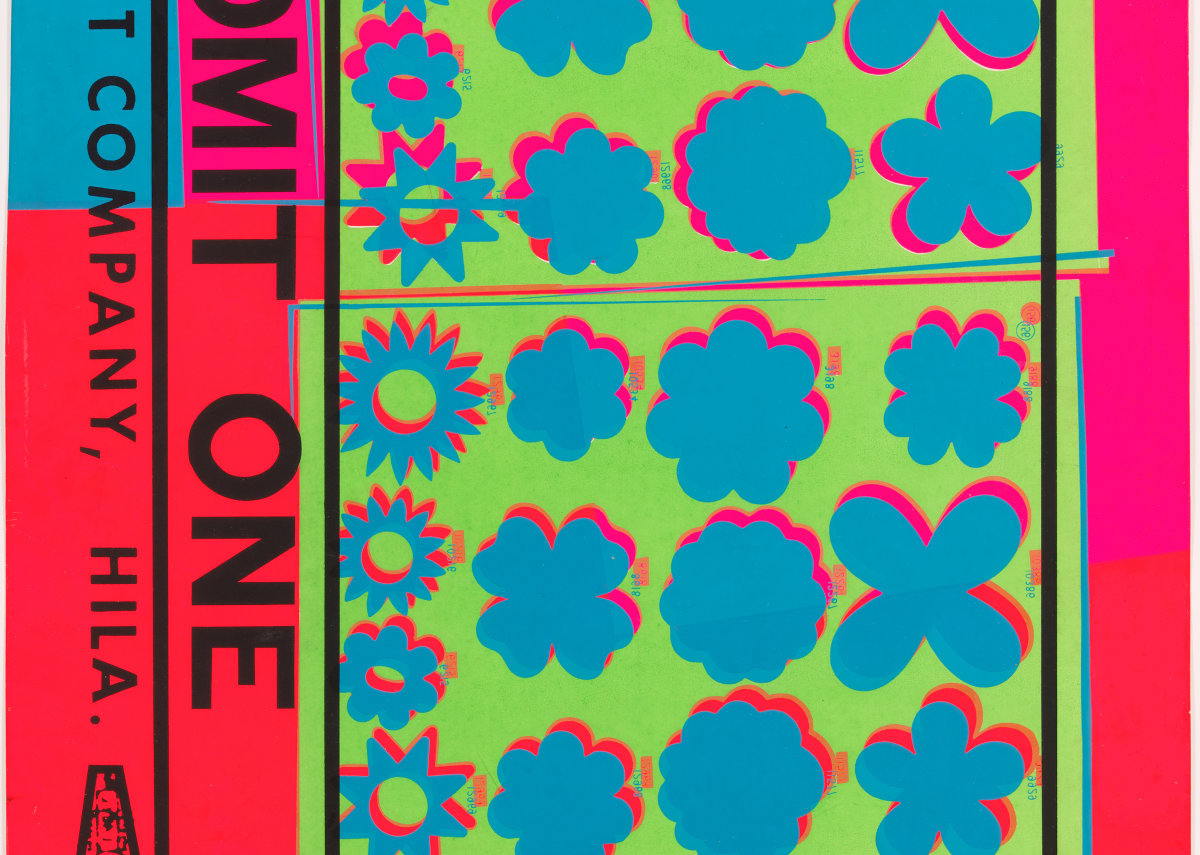

Kusama began her Infinity Net paintings in the late 1950s. In these works, she covered large canvases with fields of dots, creating subtle color and shading variations, usually on a white ground. The origin of the dots lies in Kusama’s history of mental illness. The artist recalls one of her first hallucinations, at the age of ten:

“One day, looking at a red flower-patterned table cloth on the table, I turned my eyes to the ceiling and saw the same red flower pattern everywhere, even on the window glass and posts. The room, my body, the entire universe was filled with it, my self was eliminated, and I had returned and been reduced to the infinity of eternal time and the absolute of space.” (2)

These hallucinatory patterns came to dominate much of Kusama’s work. As the artist lost herself in a sea of dots—she described her process as one of “self-annihilation” and was often photographed in front of her works dressed in colors similar to the canvases, seeming to disappear into the painted environment—it can also be argued that the labor-intensive, obsessive process of creation simultaneously affirmed the existence of the artist and her hand. (3)

Born in 1929 into a prosperous family in Nagano prefecture, Japan, Yayoi Kusama began using pattern motifs in her drawing and painting at a very young age. This predilection for pattern was inspired by effects of the mental illness that is a constant throughout her life and work. This affliction left her ostracized in her native Japan, prompting her move to New York in 1958 at the age of 27. Despite being young, female, and foreign with very little knowledge of English, Kusama quickly integrated herself into the small but vibrant art world in downtown New York, building close relationships with both Donald Judd and Joseph Cornell, and sharing a studio building with John Chamberlain, Larry Rivers, and On Kawara.

In the late 1960s, Kusama expanded her practice to include politically- and socially-minded performance art and happenings staged at art-world mainstays such as the Venice Biennale and New York’s Museum of Modern Art. These events had a strong anti-establishment message, and often scandalized art world viewers and press alike. She also began creating sculptures and installations. The Accumulation pieces feature everyday objects such as furniture, appliances, shoes, and handbags covered in soft phallic protrusions that are both comical and unsettling. In another series, she brings her investigation of pattern into three dimensions beginning with Infinity Mirror Room (1965), a small mirrored space filled with polka-dotted soft sculptures that seem to extend into infinity. In these works and others, Kusama merges concerns of the body, the self, and the infinite through an investigation of her own personal psychology.

Kusama resettled in Japan in 1975, and voluntarily became a permanent resident at Seiwa Hospital in Tokyo in 1977. She continues to create works in a nearby studio, producing paintings and sculptures in her characteristic bright colors and obsessive patterns. Following a major critical revival in America in the late 1980s, many retrospectives and large exhibitions of her work have solidified her renewed reputation, including exhibitions at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo’s Museum of Contemporary Art, Madrid’s Museo Reina Sofia, and London’s Tate Modern, as well as solo presentations at the Venice, São Paulo, and Taipei biennales.

1. Akira Tetehata, “Akira Tatehata in conversation with Yayoi Kusama,” in Yayoi Kusama. (London: Phaidon, 2000), 8.

2. Yayoi Kusama, quoted in Laura Hotpman, “Yayoi Kusama: A Reckoning,” in Yayoi Kusama. (London: Phaidon, 2000), 35.

3. Laura Hoptman, ibid.