“Today let's look at everything as though we have never seen it before.” –Dusti Bongé

An abstract expressionist painter, and Mississippi’s most acclaimed modernist artist of the post-war era, Dusti Bongé had a remarkable career that connected the vibrant art communities of Biloxi, Mississippi, New Orleans, and New York. She was one of the pioneering women artists represented by the Betty Parsons Gallery, alongside Judith Godwin, Perle Fine, Agnes Martin, Anne Ryan and Hedda Stern. A single mother who chose to reside and create work outside the New York art scene, while raising her son in her hometown of Biloxi, Bongé broke boundaries and challenged stereotypes, forging a singular path to success. Her paintings fuse the influences of the New York School with colors and forms inspired by the Gulf Coast.

An abstract expressionist painter, and Mississippi’s most acclaimed modernist artist of the post-war era, Dusti Bongé had a remarkable career that connected the vibrant art communities of Biloxi, Mississippi, New Orleans, and New York. She was one of the pioneering women artists represented by the Betty Parsons Gallery, alongside Judith Godwin, Perle Fine, Agnes Martin, Anne Ryan and Hedda Stern. A single mother who chose to reside and create work outside the New York art scene, while raising her son in her hometown of Biloxi, Bongé broke boundaries and challenged stereotypes, forging a singular path to success. Her paintings fuse the influences of the New York School with colors and forms inspired by the Gulf Coast.

Born Eunice Lyle Swetman in 1903, Bongé grew up among the natural beauty of a Southern coastal city, an environment which later provided inspiration for her abstractions. After graduating from Blue Mountain College in Mississippi in 1922, she moved to Chicago to pursue a career as an actress. There she met Archie Bongé, a student at the Art Institute of Chicago. While Archie went on to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, Bongé’s role in a touring theater production took her to New York City in 1924, where she continued to perform in vaudeville, dramas, musicals and in silent movies produced at Astoria Studios in Queens. In 1925, Archie moved to New York, where he enrolled at the Art Students League and the Grand Central School of Art, and he and Bongé resumed their relationship.

In 1928, Bongé created her first artwork, a pastel floral still life, as a surprise gift for Archie following an argument. Impressed with the drawing, he encouraged her to continue drawing and painting, instructing her informally and introducing her to artists, galleries, curators, and critics. He recommended that she not to dilute her own vision with formal training, advice she largely followed throughout her career. Dusti and Archie married in 1928 and the following year their only child Lyle Bongé was born. The pregnancy brought about an abrupt end to Bongé’s acting career, forcing her to withdraw form a theatrical production she was working on. She never returned to the stage.

In 1934, responding to the impact of the Depression on New York City, Dusti and Archie decided to move to Biloxi so that Archie could build a larger studio and the family could establish a small farm. During this time, they developed friendships with many other local artists including Mississippi painter Walter Anderson, New Orleans painter Paul Ninas, and Ojo Ohr, the son of acclaimed Biloxi potter George Ohr. The artistic life they had begun to create was tragically cut short when Archie fell ill in late 1935 and died of an undiagnosed illness (possibly ALS) in November of 1936.

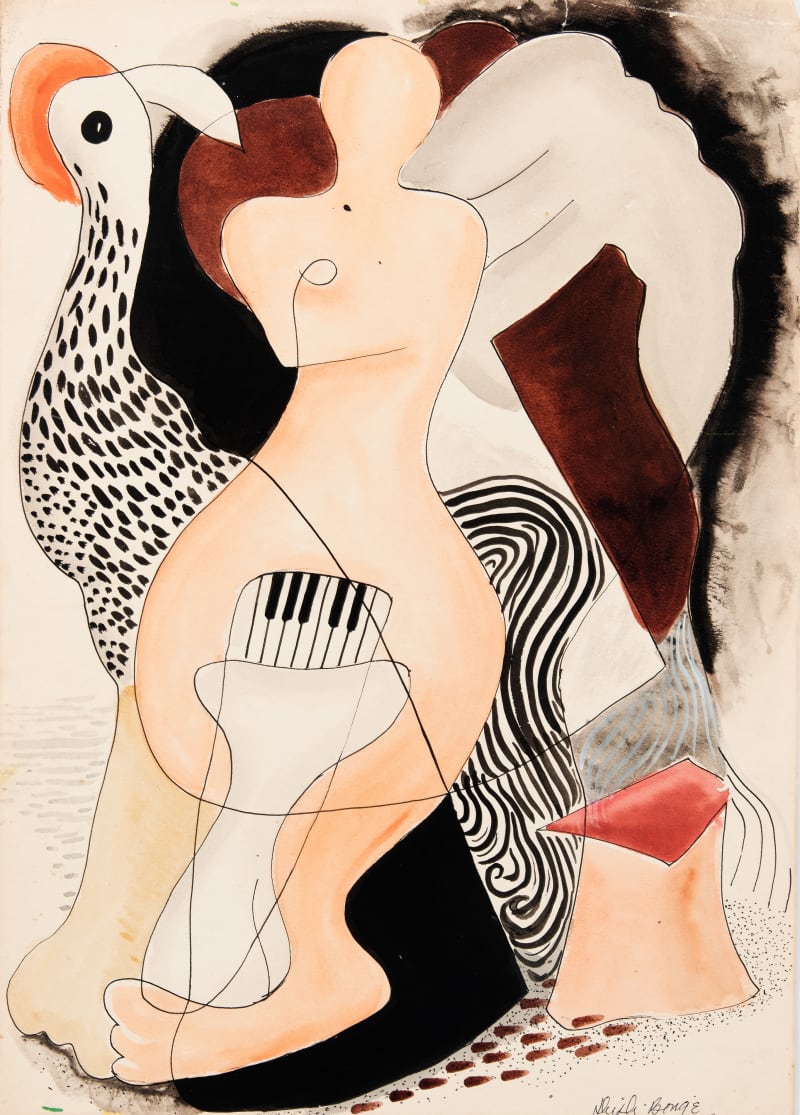

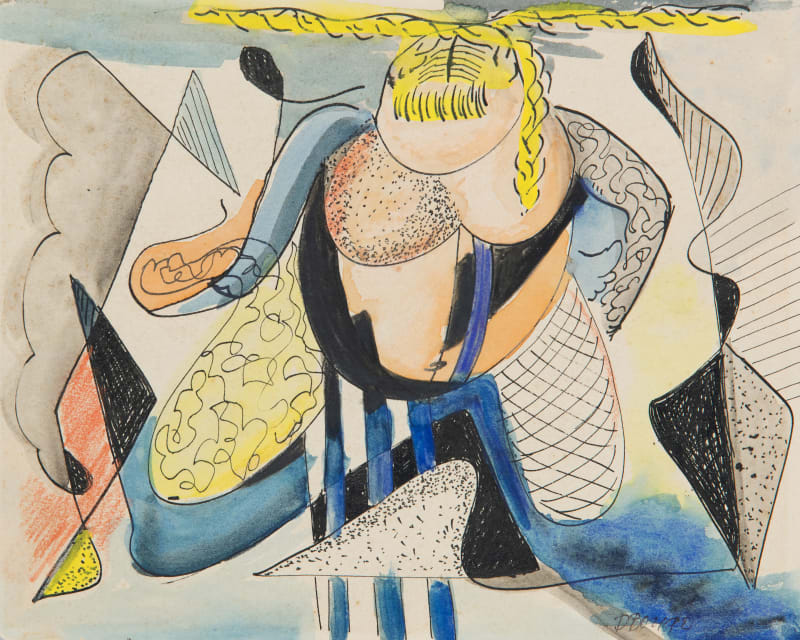

Following Archie’s death, in search of a new direction, Bongé began developing her own career as professional painter, while raising Lyle, who was now seven years old. Working out of Archie’s studio, she turned to the familiar beauty of her hometown for inspiration, sketching and painting the Victorian architecture, industrial seafood factories, shipyards, and wildlife. At the same time, she remained engaged with new influences shaping American art, including Cubism, Surrealism, and the philosophies of Freud and Jung. Her paintings from the late 1930s and 1940s are semi-abstract regionalist scenes, which reflect her understanding of Cubist structure and Fauvist color. These works would have been at home in Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery alongside examples by American modernists Stuart Davis, Alfred Maurer, and Georgia O’Keeffe. She exhibited in New Orleans and Biloxi and first presented her work in New York at the Contemporary Arts Gallery in 1939.

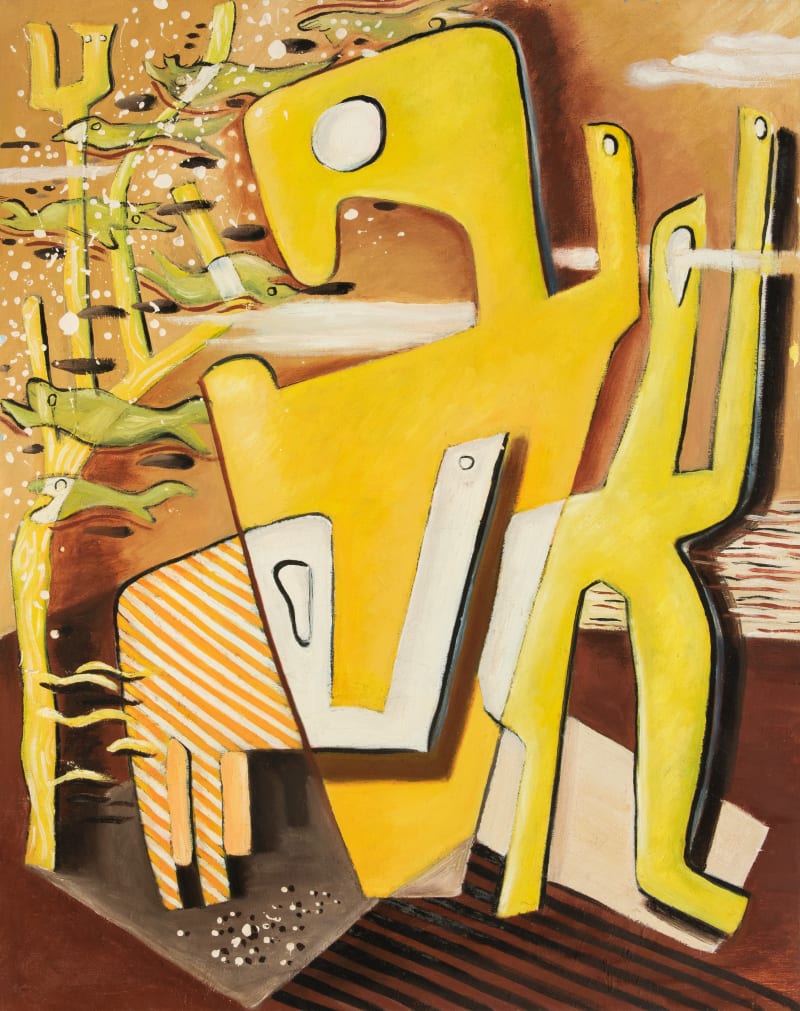

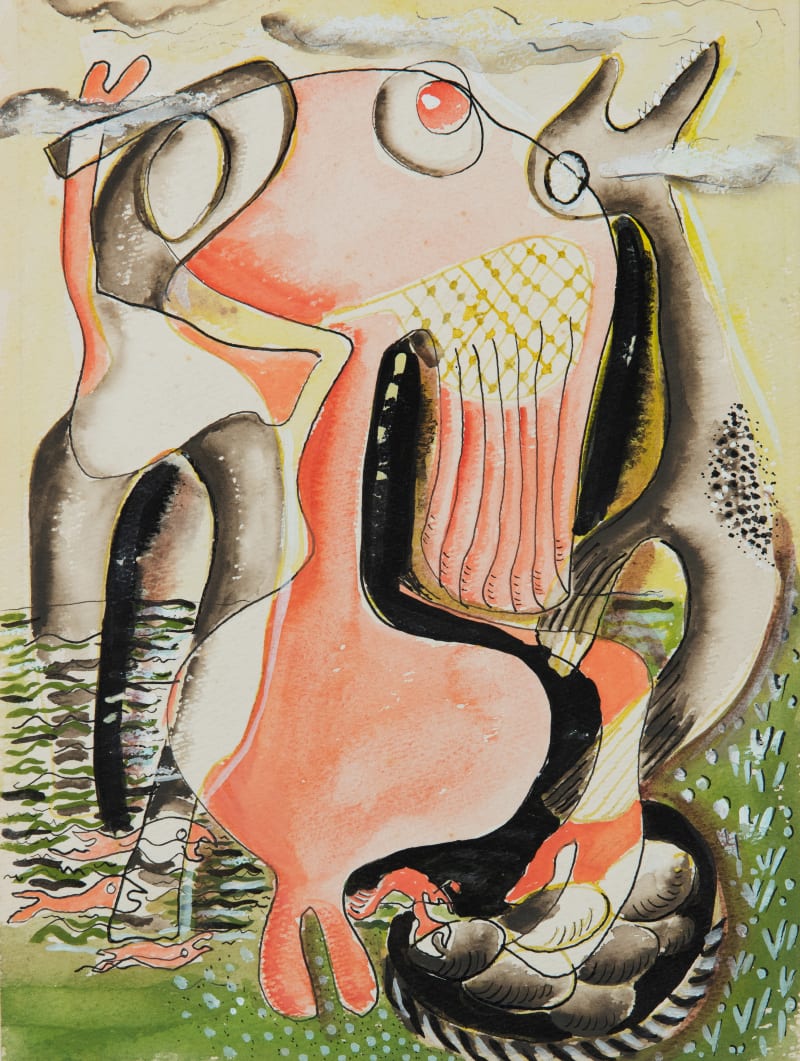

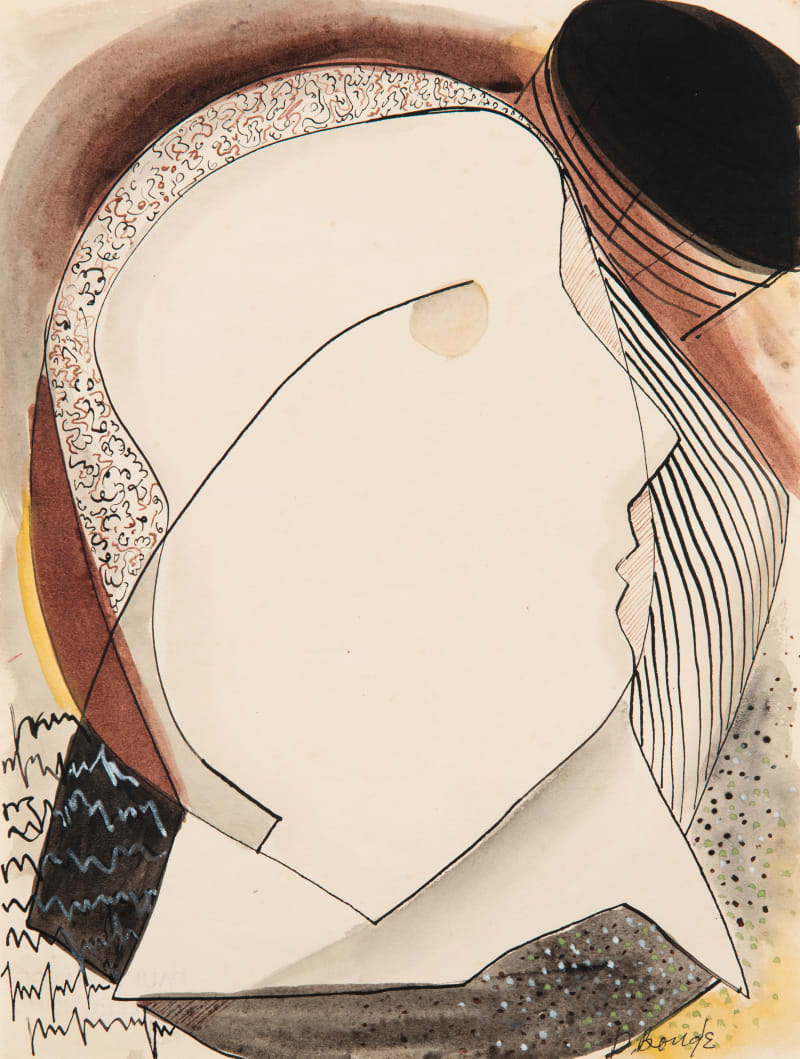

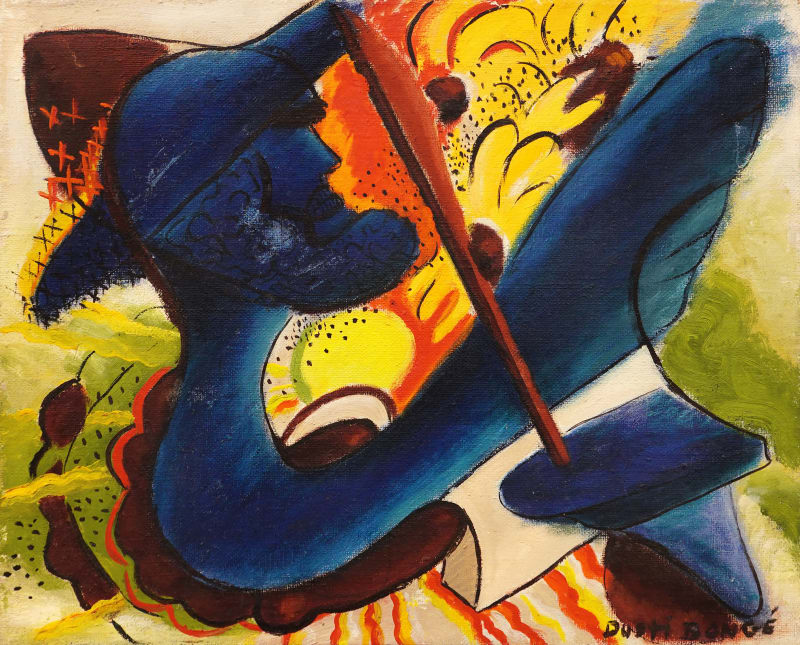

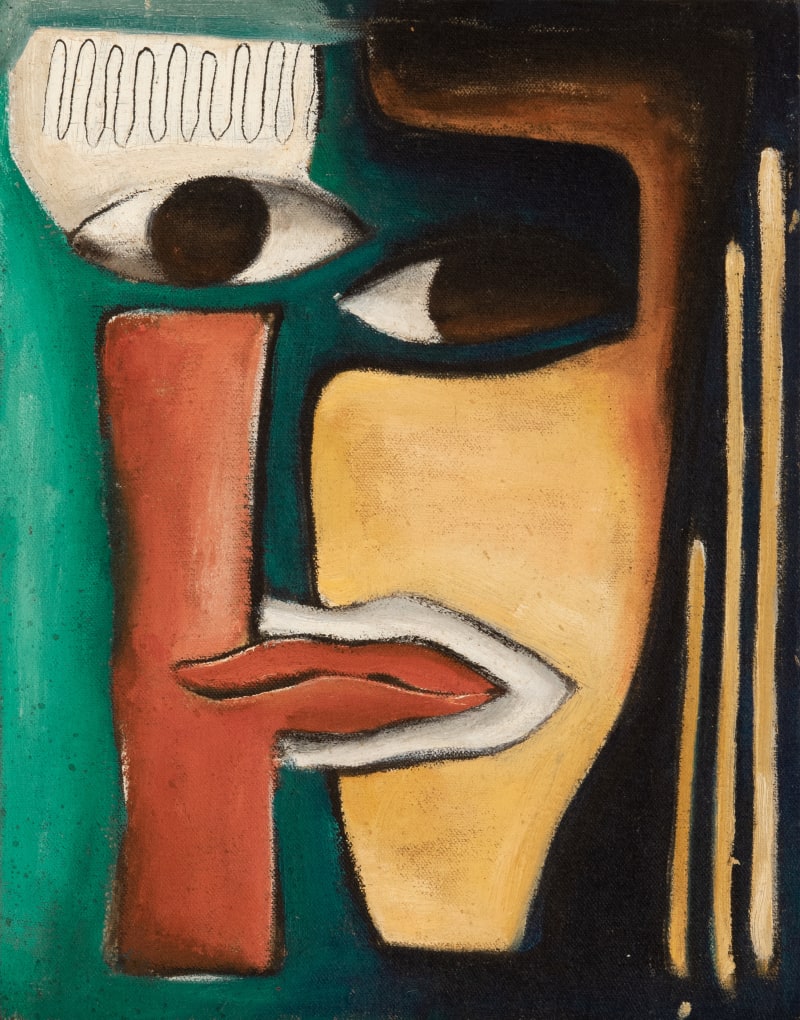

Throughout the 1940s, Bongé became more intensely involved with Surrealism and often described painting images she had seen in dreams or tapped from her unconscious: “As I changed my style from realistic to the abstract, dreams formed a bridge between the two…Many times in the past I have dreamed complete canvases. I see, in my dreams, not only the feeling that I want to convey, but the colors that I want to use and their exact location on the canvas.” (1) Her paintings of the mid-to-late 1940s featured elongated biomorphic figures or floating mask-like faces. By the early 1950s the figures became flattened and abstracted into an arrangement of forms that evoked both the human body and oversized hieroglyphics. Around this time, Bongé’s brushstrokes became more gestural and her mature Abstract Expressionist style emerged, bringing together aspects of cubist structure, surrealist imagery, and subtle references to the shapes, light, and flora and fauna of Biloxi and New Orleans.

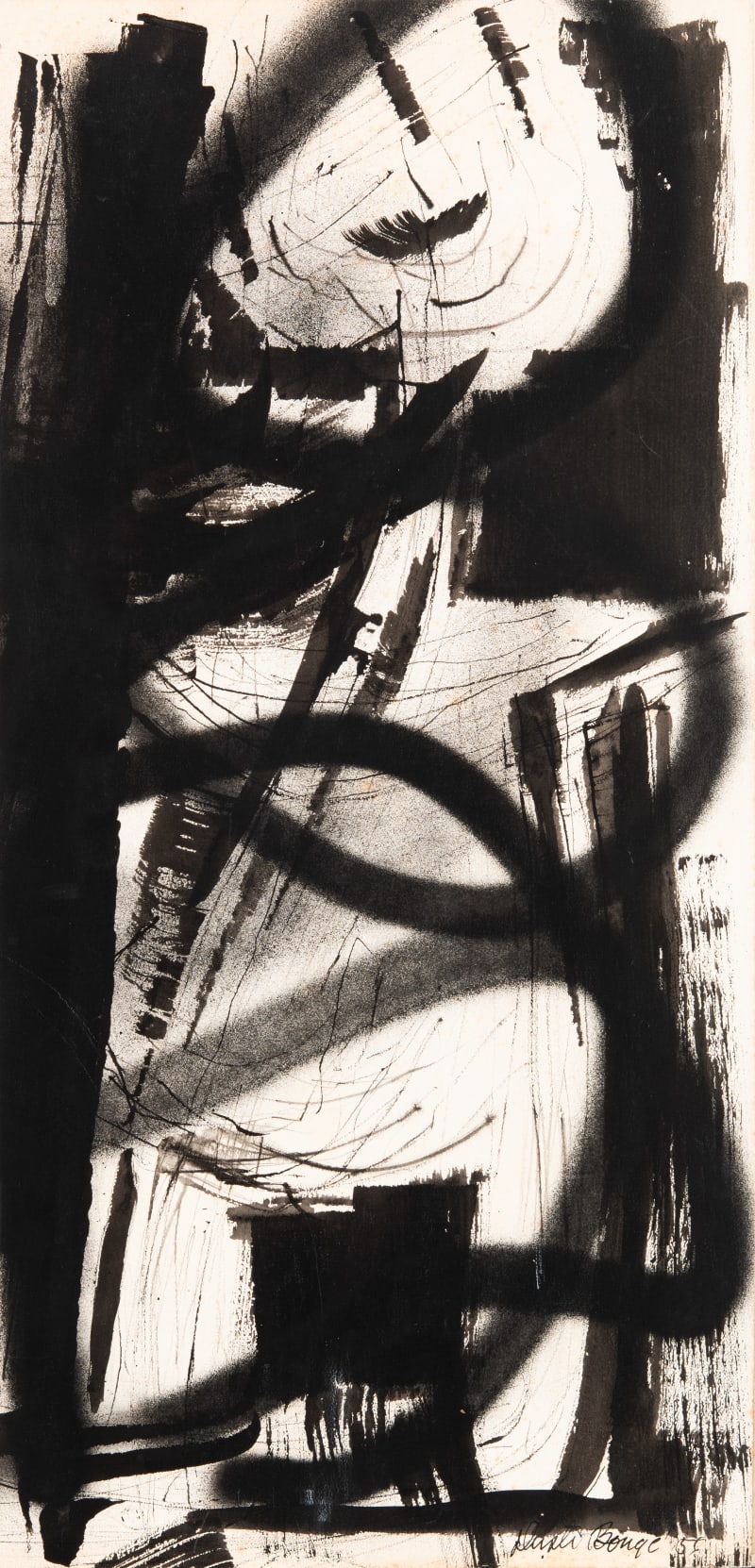

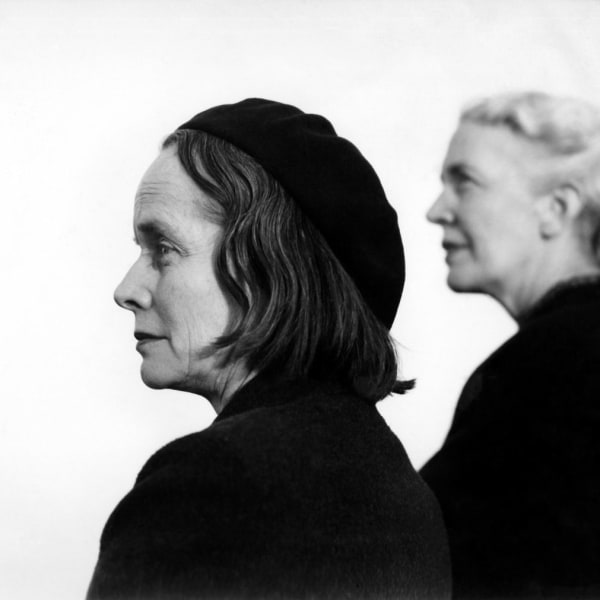

Throughout these years, Bongé retained a connection to New York artistic circles and during one visit in 1945 was introduced to Betty Parsons while presenting her work at the Mortimer Brandt Gallery. Parsons was impressed with Bongé’s painting and, when she opened her own gallery in 1946, exhibited several of Bongé’s watercolors. Bongé and Parsons became good friends and, in the spring of 1954, they spent several weeks together in Biloxi, creating art side by side in Bongé’s studio. They then traveled together throughout Mexico during the summer of 1954, accompanied by Bongé’s friend, photographer Jack Robinson. Although Bongé had previously visited Mexico in 1952, this second trip in the company of fellow artists, was incredibly influential, informing the development of a more expressive, unconstrained approach. She noted of this period: “During the 1950s, I began painting totally in the abstract. It gave me great joy. I began to work with very large canvases and brushes. They seemed to give me the freedom that I needed.” (2) In the mid 1950s, she joined Betty Parson’s stable and was featured in solo exhibitions in 1956, 1958, 1960, 1962, and 1975.

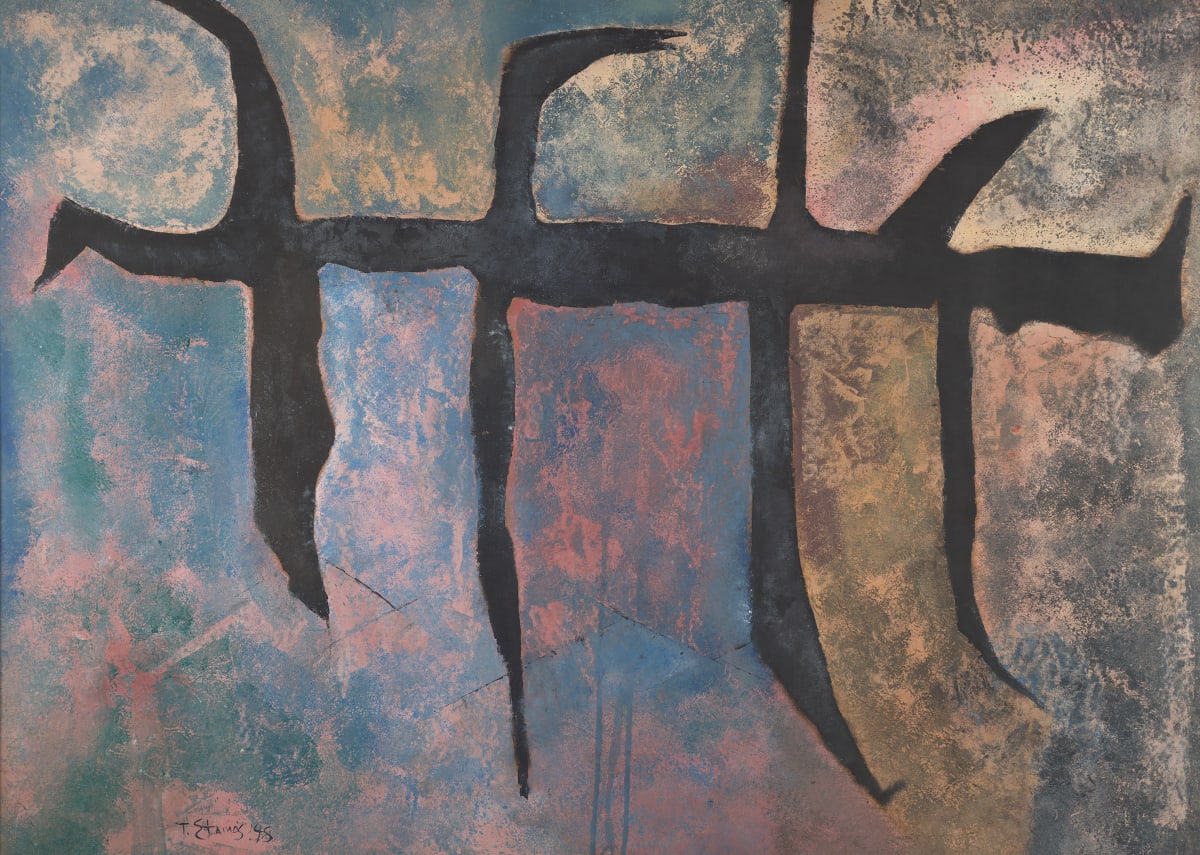

At the same time, Bongé remained active in the New Orleans art scene, maintaining an apartment there and taking art classes at the 331 Gallery School in the French Quarter. She became an important point of connection between the New York and New Orleans artistic communities, developing friendships with both Theodoros Stamos, who visited her in Biloxi, and New Orleans painter Goerge Dunbar, whom she introduced to Parsons. Through Lyle, who had attended Black Mountain College and become a well-regarded photographer, Dusti met many of the artists and writers of the Black Mountain group including Jonathan Williams, M.C. Richards, and John Cage. Through Parsons, Cage, and M.C. Richards, Bongé became interested in Zen Buddhism, and read Eugen Herrigel’s book Zen and the Art of Archery, which Parsons had given to her.

In the later part of her career, Bongé forcefully explored new ideas, traveling extensively and experimenting with techniques and materials. In 1964, she embarked on an adventurous six-month world tour on a freighter. She visited Libya, Lebanon, Egypt, India, Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, Peru, and Panama. When she returned from her travels, she began a series of small mixed-media sculptures that evoked children’s building blocks. She continued to create large-scale oil paintings, and in the 1970s began working with vibrantly-colored fiberglass. She also sculpted clay pots and bowls and produced a series of brightly colored watercolors and collages. In the 1980s she used Joss paper, gold squares of bamboo rice paper burned in traditional Chinese ceremonies, as grounds for her watercolor painting. Bongé created Joss paper watercolors, often working on an intimate scale, until two years before her death in 1993 at age ninety.

Over the course her career, Bongé exhibited in numerous group and solo exhibitions. In addition to her exhibitions at Betty Parsons, she was featured in group shows at the Mississippi Museum of Art (1953), Museum of Modern Art New York (1955), Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Texas (1956), Dallas Museum of Art (1956), Whitney Museum of Art (1956), Museo Nacional, Havana, Cuba (1956), Brooklyn Museum of Fine Arts (1959) and Birmingham Museum of Art (1959). Following her death, she received major retrospectives at the Walter Anderson Museum of Art, Mississippi (1995 and 2013), Mobile Museum of Art, Alabama (2006), and most recently the traveling exhibition Piercing the Inner Wall: The Art of Dusti Bongé organized by the Ogden Museum of Southern Art (2019-21). Her paintings are in numerous public collections including the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, the Mississippi Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the National Museum of Women in the Arts.

(1) Dusti Bongé, “The Life of an Artist” quoted in J. Richard Gruber, Dusti Bongé Art and Life: Biloxi, New Orleans, New York (Dusti Bongé Art Foundation: Biloxi, MI, 2019), 109.

(2) Dusti Bongé, “The Life of an Artist” quoted in Dusti Bongé Art and Life: Biloxi, New Orleans, New York, 224.

Works