Hines prompted viewers with his wrappings to reevaluate form and space, lending surprisingly new sculptural qualities to architecture.

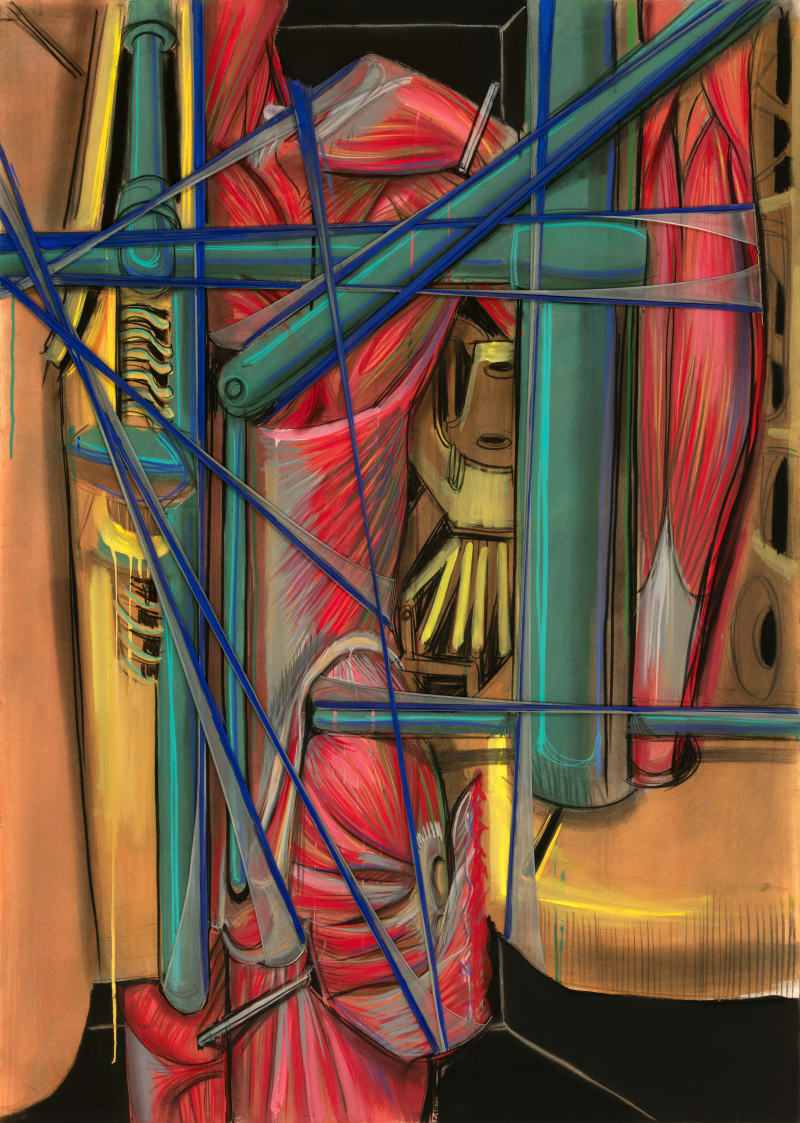

As the only artist to ever wrap buildings in Manhattan, Francis Mattson Hines (1920-2016) is known for his paintings, sculptures, and public art projects, especially the wrapping of the Washington Square Arch in 1980. His work positioned him at the forefront of expressionist experimenting with wrapping, which allowed him to imbue his works with literal and metaphoric tension and kineticism. Though his work received critical acclaim during his lifetime, Hines slipped into obscurity toward the end of his life. Fortunately, most of his work was salvaged outside of his barn studio a year after his death.

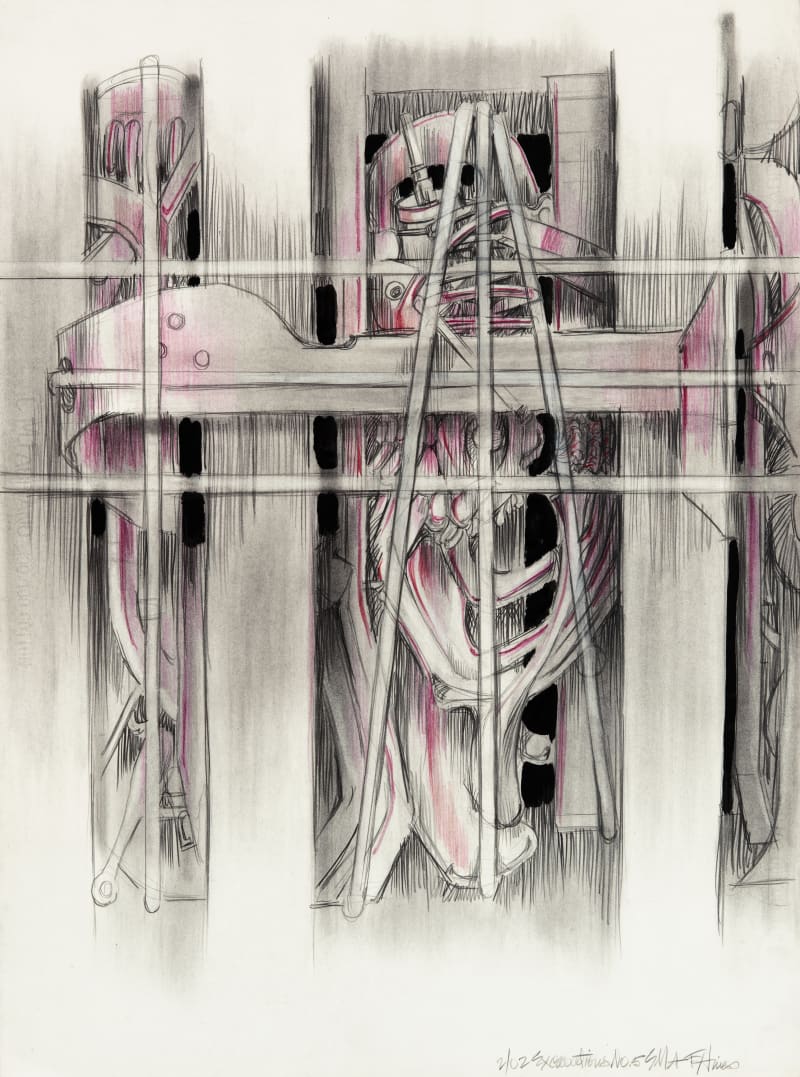

Today, Francis Hines is best known for wrapping the Washington Square Arch in 8,000 yards of white polyester fabric in 1980. Hines was invited to wrap the Arch by New York University, as part of their campaign to raise funds to restore the monument after decades of graffiti blight. Described as “a giant bandage for a wounded monument,” the wrapping was an extraordinary undertaking that involved a team of 23 people stretching and crisscrossing each piece of fabric tightly into a geometric pattern. In 2017, on the 50th anniversary of the “Art in the Parks” program run by New York City’s Parks, Recreation, and Cultural Affairs Agency, Hines’ wrapping of the Arch was chosen as one of the top ten public art installations to have taken place in NYC.

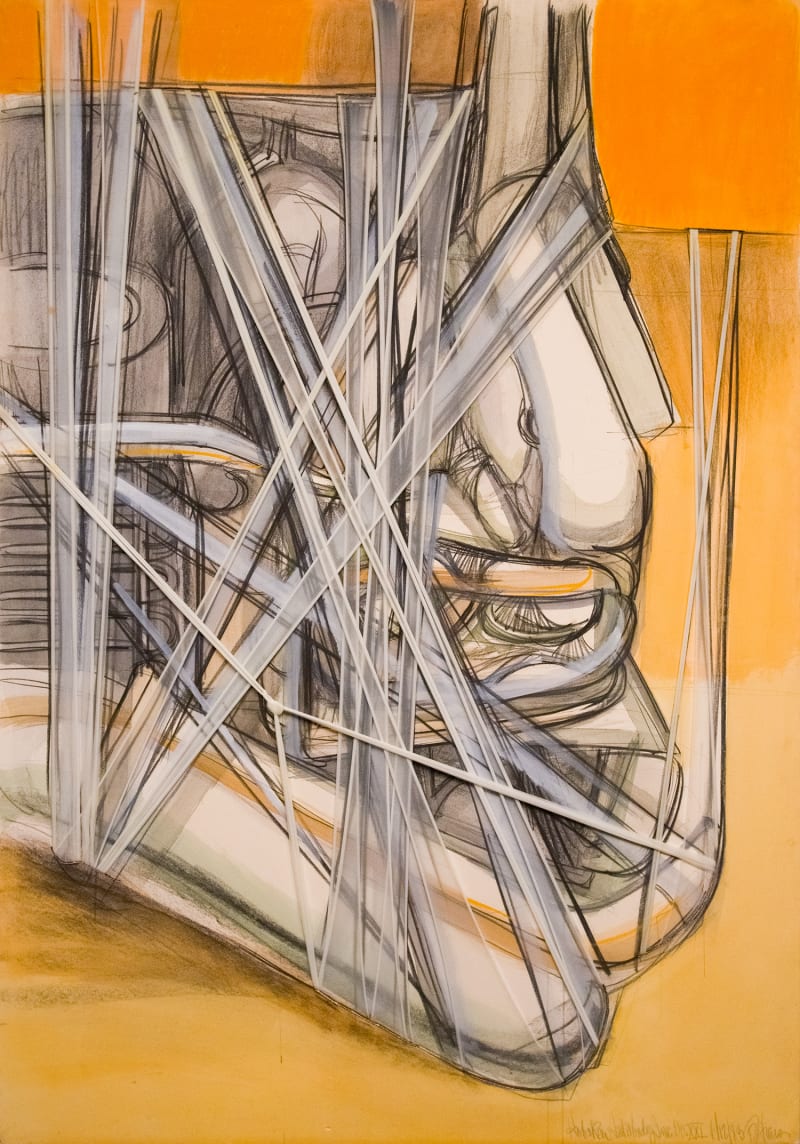

After the Arch wrapping, in 1981 Hines installed Suspended Sculpture in the New York Port Authority Bus Terminal and a year later in 1982 he performed an unauthorized “guerilla wrapping” of a section of the old Westside Elevated Highway while it was in the process of being demolished. The white synthetic fabric was stretched between the highway’s last remaining massive vertical and horizontal iron girders. In 1983 his Celebration in Flight was installed at the JFK International Airport Arrivals Building in celebration of its 25th anniversary. It was composed of 825 yards of red parachute nylon extending 100 x 50 ft—and was in conversation with Alexander Calder’s nearby 45-foot mobile, .125 from 1957 (later re-named Flight).

Like Christo, Hines prompted viewers with his wrappings to reevaluate form and space, lending surprisingly new sculptural qualities to architecture. But whereas Christo was a conceptualist who emerged from the Dadaist tradition of Man Ray and covered structures in translucent polyethylene sheets before bounding them with ropes, Hines, on the other hand, developed a completely different approach to wrapping from that of Christo. As art historian Peter Falk wrote, “Hines’ pursuit was aesthetic, not conceptual. It was not about loosely wrapping up a form. It was instead about tightly weaving diaphanous synthetic fabrics into geometric patterns, stretching them over a building’s facades under hundreds of pounds of pressure.”

Born in Washington D.C. in 1920, Hines attended the Cleveland School of Art (now the Cleveland Institute of Art) before serving in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers during World War II. Following the war, Hines settled in New York City, working as a commercial illustrator in addition to pursuing painting as a hobby. In the 1950s, he held the position of chief commercial artist at G. Fox & Co, one of the largest private department stories in the country at the time. In the 1960s, his personal artistic practice started to receive attention, and in 1965, he had his first solo exhibition at the Smolin Gallery, an avant-garde art venue on 57th Street. Around this time, Hines moved to Watertown, Connecticut, where he converted a barn into a large studio and worked on his personal artistic projects until his death. His wrapped sculptures were shown at the Stewart Neill Gallery in SoHo multiple times in the 1970s and he was represented by the Vorpal Gallery in SoHo from 1984 until the gallery’s closing in 1997.

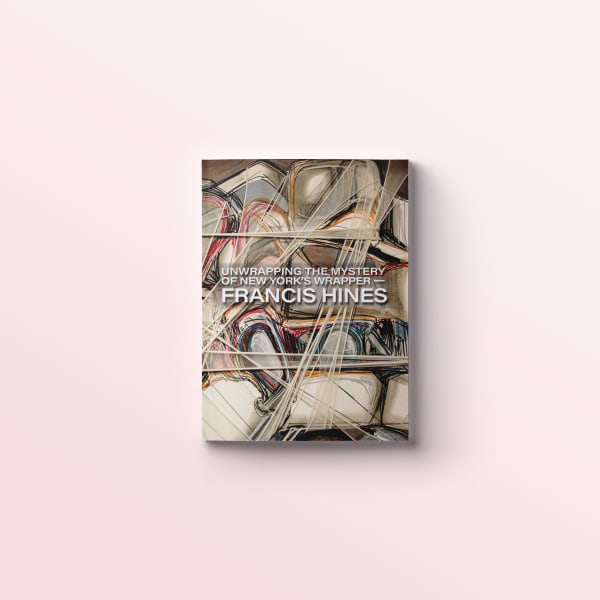

Following his death in 2016, Hines’ house and barn studio were cleared and the contents were placed into dumpsters. A car mechanic named Jared Whipple was alerted by a friend to of these dumpsters and was intrigued by the work. When he entered the barn and saw what remained of Hines’ studio, Whipple decided to salvage the work that had not yet been destroyed and embarked on a mission to piece together the artist’s story. In 2018, having learned as much as he could about Hines, Whipple contacted Peter Falk, an art historian with an expertise in rediscovering significant American artists who have been forgotten over time. Falk then worked with Hollis Taggart and his team to organize an exhibition in 2022 devoted to Hines’ works entitled “Unwrapping the Mystery of New York’s Wrapper.”

Works