Through Minimalism, Iwamoto saw the potential for a method by which he could explore and express a universal truth

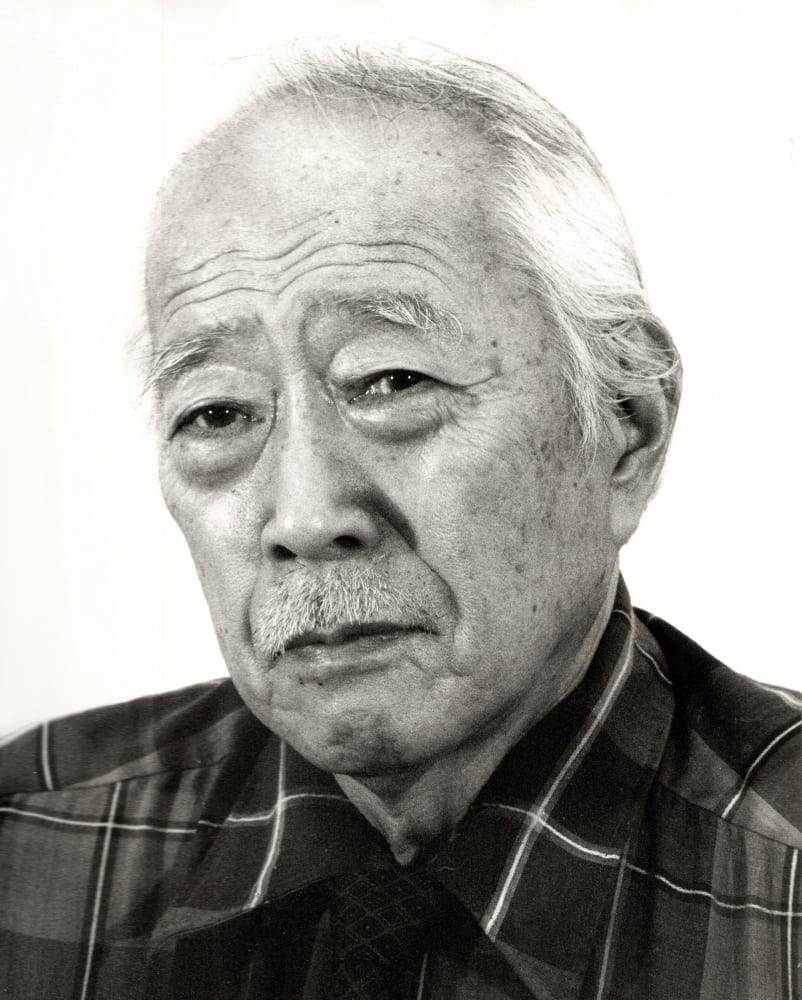

Born in Hawaii in 1927 to Japanese Buddhist parents, Ralph Iwamoto witnessed the bombing of Pearl Harbor as a teenager in 1941. Like many other artists of his generation who grew up in Hawaii, Iwamoto served in World War II and afterwards moved to New York City in 1948. There, he enrolled in the Art Students League with the support of the GI Bill and studied with abstract artists Vaclav Vytlacil and Byron Browne, immersing himself in the dynamic milieu of the 1950s art scene. Iwamoto’s early work leaned heavily towards organic forms, muted colors, and techniques found in traditional Japanese art. His first exhibition in New York took place in 1955, alongside Louise Nevelson and Alfred Leslie. Three years later, his work was included in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s annual.

From 1957 to 1960, Iwamoto worked as a security guard at the Museum of Modern Art, which allowed him the opportunity to spend long periods of time viewing surrealist and other modern paintings. His work from the 1950s reflect a deep interest in surrealist imagery and ideas inspired by the works of Wifredo Lam, Rufino Tamayo, and Pablo Picasso. Trafficking in abstract organic forms of flora and fauna, Iwamoto’s paintings from this period evoke an “invented taxonomy of kingdom hybrids,” as noted by curator Jeffrey Wechsler. The artist’s hybrid animal-vegetation figures nod to the tropical diversity of the artist’s birthplace as well as perhaps his time designing and creating arrangements for various New York department stores using fresh flowers and orchids flown in from Hawaii. This series of works synthesize the geometric abstraction of Cubism, the surrealist style, and the flat, planar characteristics of traditional Japanese art.

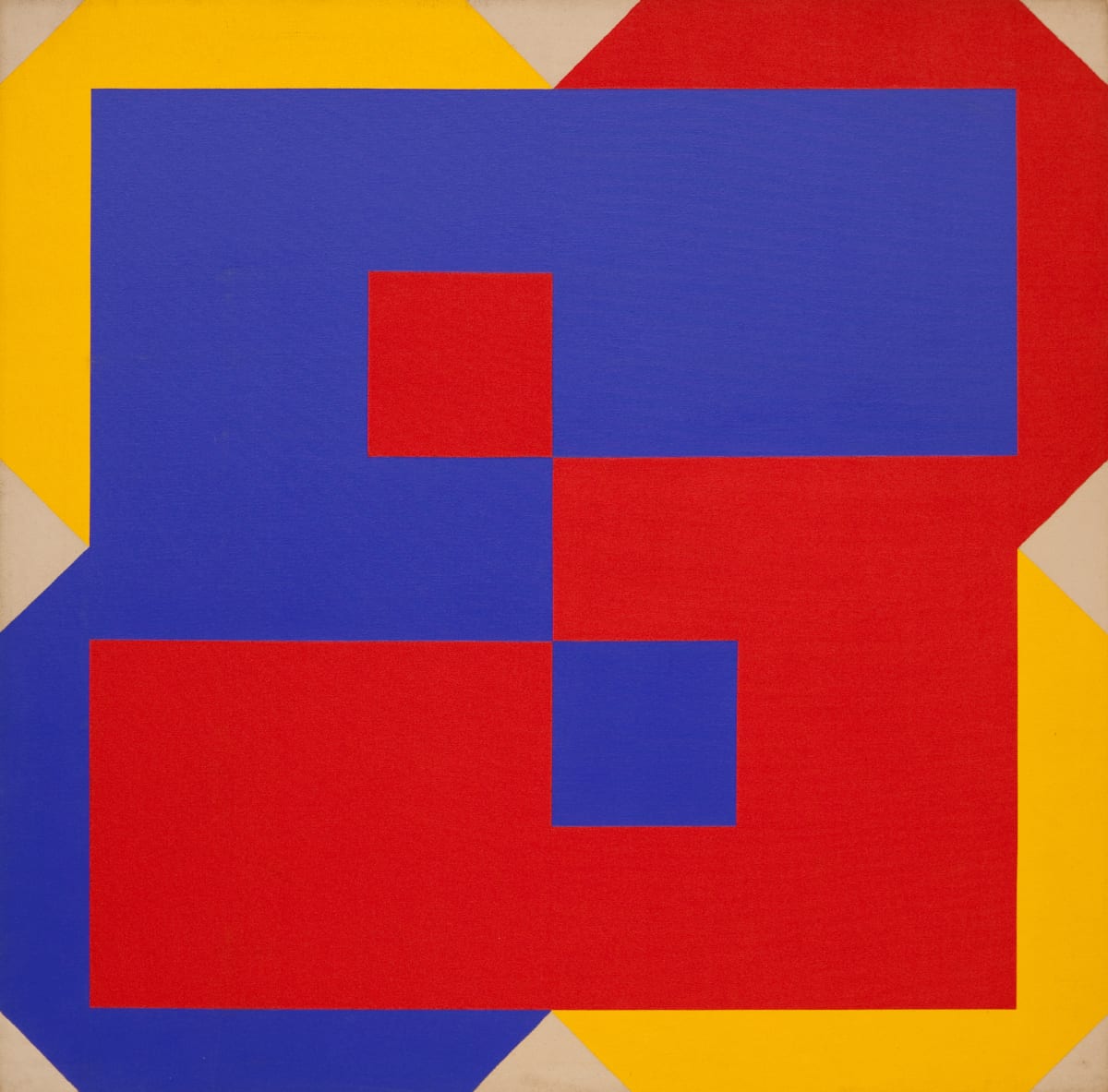

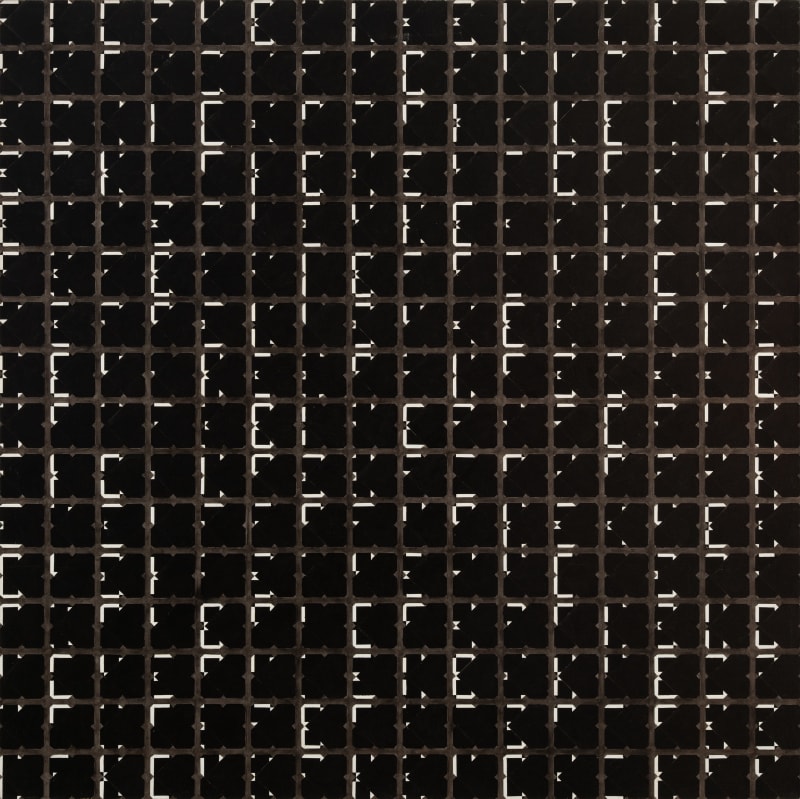

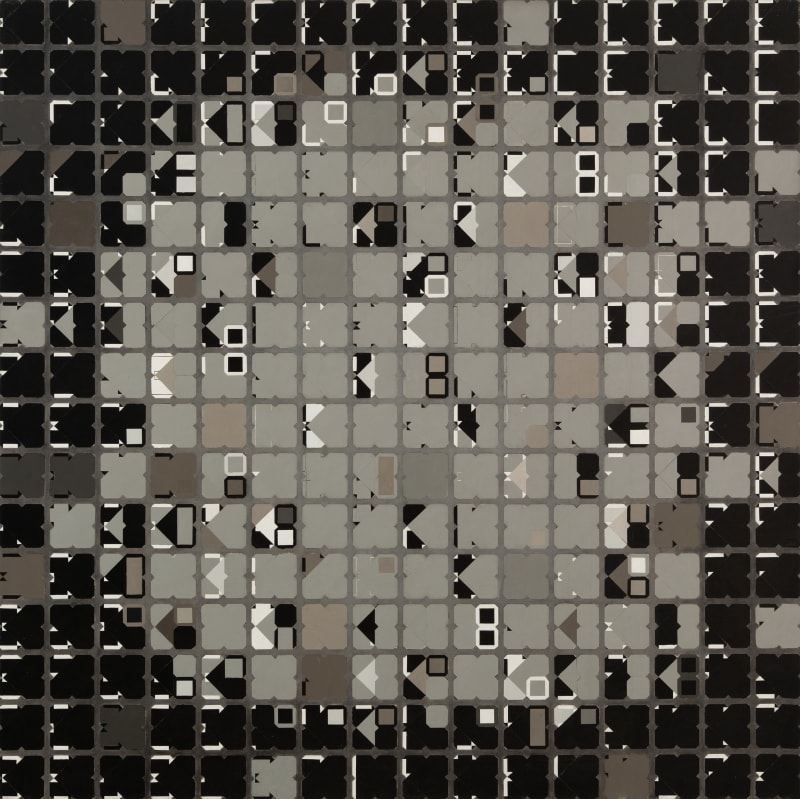

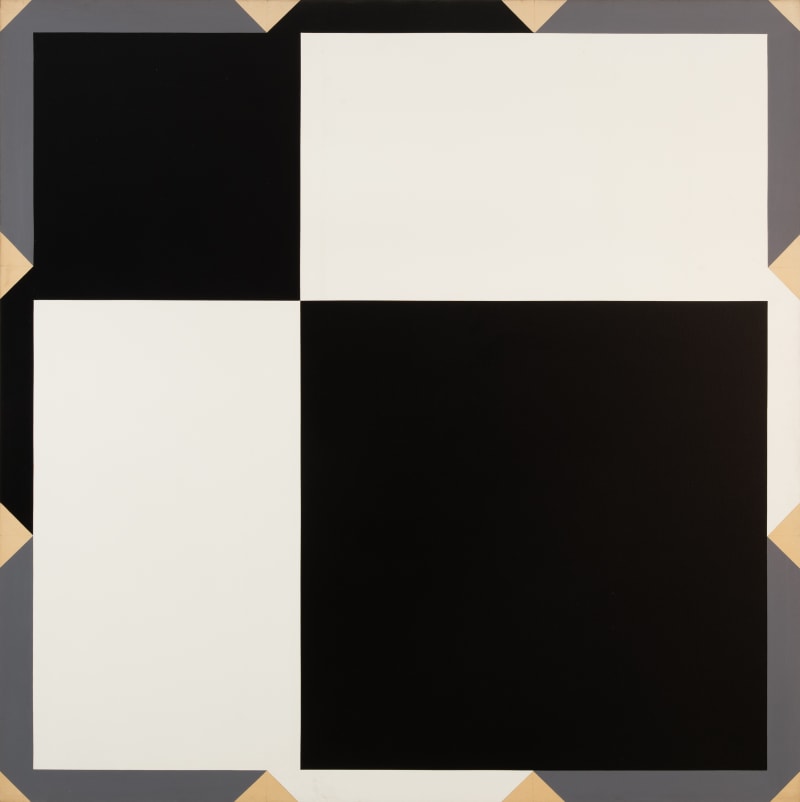

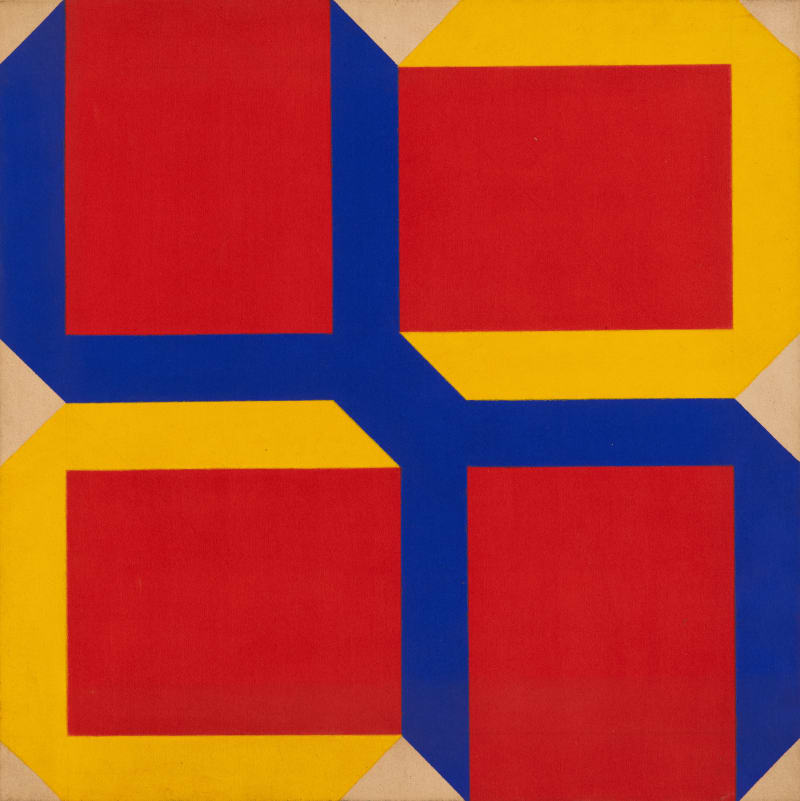

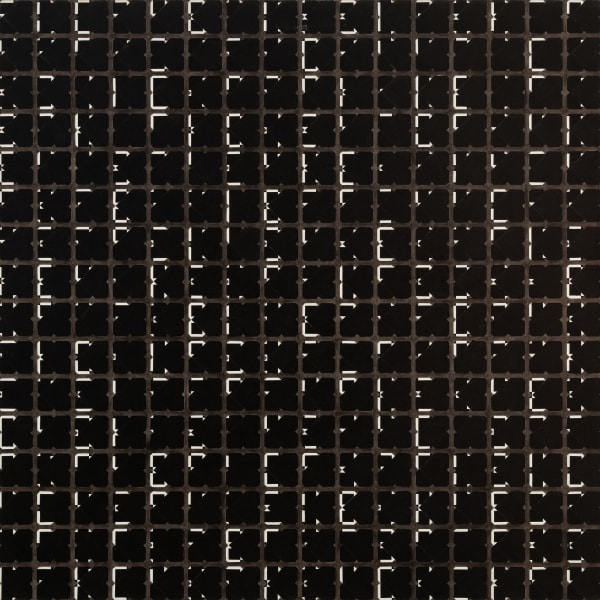

While working as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art, Iwamoto formed close friendships with artists Sol LeWitt, Robert Ryman, and Dan Flavin, who would later go on to become the core group of the Minimalism movement. Influenced by their stylistic and formal innovations, Iwamoto began experimenting with pure color and form and rigorous geometricism in the 1960s. Through Minimalism, Iwamoto saw the potential for a method by which he could explore and express a universal truth and in the early 1970s, he began to work specifically with the octagon as his “shape within a grid.” Inspired by his friend LeWitt’s right angle and left angle compositions, as well as the work of Piet Mondrian and Josef Albers, Iwamoto mined ways to syncopate a grid through seemingly infinite permutations of an octagon and a minimal color palette. He often worked with groups of four (which he terms “QuarOctagons”), eight (“Octagon Concepts”), and sixteen octagons (“Factors”) in grid format and went on to use the octagon in increasingly complex arrangements. In 1989, St. Mary’s College held a retrospective of his octagon paintings. In the later decades of his career, his style shifted to more kaleidoscopic compositions. He died in 2013.

Works