Underpinning Cajori's painting practice were enduring concerns around space and form, and the construction of pictorial space through the architecture of color planes or what he called the "swift continuum of space."

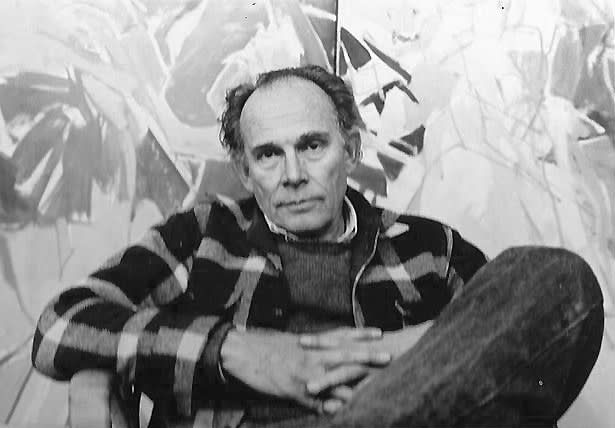

A founding member of the Tanager Gallery and a second generation Abstract Expressionist, Charles Cajori (1921-2013) led an extraordinary career during a critical juncture of postwar American art history. After arriving in New York in 1946, he and a small group of artists founded the Tanager Gallery on 10th Street in 1952, which became a crucial meeting point and exhibition space for the growing New York School of artists. Cajori was also a founder in 1964 of the New York Studio School, a unique “atelier” art school that still exists today.

Underpinning his painting practice were enduring concerns around space and form, and the construction of pictorial space through the architecture of color planes or what he called the "swift continuum of space." Cajori passionately experimented with how the shifting of colors can add an urgency of rhythm and a quality of light. He called the surface of a canvas or paper a “spatial arena” or a “field of energy,” in which complex relationships and tensions arise and “undergo constant reassessment.” (1) Unexpected configurations are brought into being, producing what he termed “dislocations from the ‘normative.’” Such harmony of forms, he believed, “cannot be arrived at rationally. . . It can’t be designed. It happens intuitively and is a final expression. This ambiguous, ongoing continuum reflects, I believe, something of our experience, of our difficulty in coming to terms with ourselves and with nature.” (2) Painting, for Cajori, was almost a metaphysical pursuit and, as one critic put it, it “demanded an almost spiritual awareness of the process of seeing.” (3) Accordingly, Cajori was particularly interested in the works of Cézanne and by what Cajori believed to be the seismic shifts in perception brought about by Cézanne. Cajori’s work grapples with the legacy of the French master, the former’s staccato, activated marks reflecting the idea that when we perceive and look at something, our eyes are never static.

A founding member of the Tanager Gallery and a second generation Abstract Expressionist, Charles Cajori (1921-2013) led an extraordinary career during a critical juncture of postwar American art history. After arriving in New York in 1946, he and a small group of artists founded the Tanager Gallery on 10th Street in 1952, which became a crucial meeting point and exhibition space for the growing New York School of artists. Cajori was also a founder in 1964 of the New York Studio School, a unique “atelier” art school that still exists today.

Underpinning his painting practice were enduring concerns around space and form, and the construction of pictorial space through the architecture of color planes or what he called the "swift continuum of space." Cajori passionately experimented with how the shifting of colors can add an urgency of rhythm and a quality of light. He called the surface of a canvas or paper a “spatial arena” or a “field of energy,” in which complex relationships and tensions arise and “undergo constant reassessment.” (1) Unexpected configurations are brought into being, producing what he termed “dislocations from the ‘normative.’” Such harmony of forms, he believed, “cannot be arrived at rationally. . . It can’t be designed. It happens intuitively and is a final expression. This ambiguous, ongoing continuum reflects, I believe, something of our experience, of our difficulty in coming to terms with ourselves and with nature.” (2) Painting, for Cajori, was almost a metaphysical pursuit and, as one critic put it, it “demanded an almost spiritual awareness of the process of seeing.” (3) Accordingly, Cajori was particularly interested in the works of Cézanne and by what Cajori believed to be the seismic shifts in perception brought about by Cézanne. Cajori’s work grapples with the legacy of the French master, the former’s staccato, activated marks reflecting the idea that when we perceive and look at something, our eyes are never static.

Though Cajori drew and painted landscapes and non-representational works in the 1940s and early 1950s, his focus throughout his career remained the figure, which began to dominate his work in the 1960s. Always working within the tension between the fixed form of the figure and the flux of perceptual reality, Cajori strove to depict the human figure with a colorful expressionism reminiscent of Matisse and de Kooning.

In the catalog for his last solo show in New York, the artist articulated his aesthetic philosophy: “First is the acknowledgment of chaos: its contradictions and wayward forces. Then the struggle for coherence. Not a coherence of illusion but one of time and space—of form. The mode of attack is improvisational, multileveled, and non-rational. The resulting structures may seem complete, but they contain a hint of another stage. New attacks are called for. Structures evolve endlessly.” This “struggle of coherence” that Cajori believed was at the heart of form is palpable in his paintings, with their energetic swaths of lines and color that seem to literally be struggling to take form, to cohere into a visually intelligible entity.

A gifted teacher who was a deep influence and formidable mentor to many, Cajori taught at Cooper Union from 1956 to 1965, at Queens College from 1965 to 1986, as well as at Berkeley from 1959 to 1960 alongside Richard Diebenkorn and Elmer Bischoff. To students he stressed the need to forego preconceived notions of seeing and instead to see spatial relationships anew: “Look at the window,” he would tell his students, “and notice how the sky clings to the pane.” (4)

Born in 1921 in Palo Alto, Cajori studied at Colorado Springs Art Center, Cleveland Art School, and Columbia University. Cajori's work is represented in many public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Hirshhorn Museum, Whitney Museum, Yale University Art Gallery, Walker Art Center, Weatherspoon Art Museum, Arkansas Art Center, and the National Academy of Design, among others. He has won numerous awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Louis Comfort Tiffany Award, a Jimmy Ernst Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and NEA and a Fulbright grant.

- Interview with Transfer Magazine, June 1988.

- “On Paper,” delivered on Panel on Drawing on October 21, 1999 at the National Academy of Design, NYC.

- John Goodrich, “Intimist Glow, Expansive Gestures: Charles Cajori,” Artcritical (December 24, 2013).

- Gerald M. Munroe, “Teaching Drawing: The Personal Approach of Charles Cajori,” The International Review published by The Drawing Society, November-December 1979.