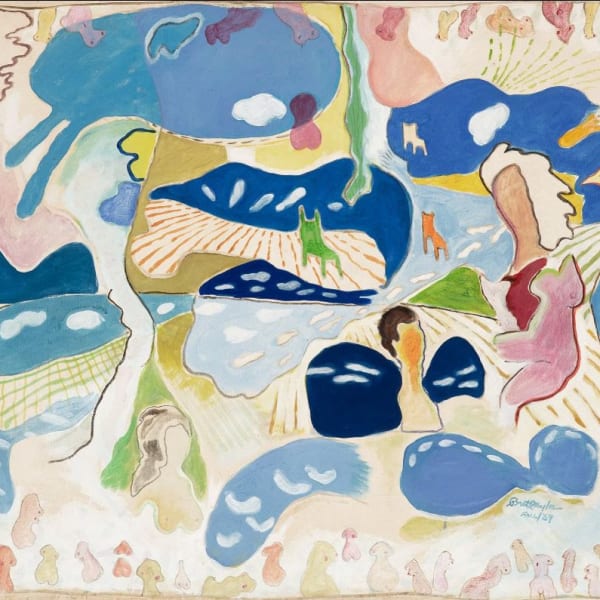

His paintings had stood out as stylistically distinctive, and he was anxious to make an impact—not only by developing a new approach to painting but by developing an entirely new philosophical approach to teaching art.

Brett Taylor’s innovative approach to painting—merging storytelling, surrealism, and figurative abstraction—had matured significantly during his undergraduate years, although he was restless at the Tyler School of Art. As the Vietnam War erupted in 1965, Taylor was preparing to leave the United States. He was not among the more than 30,000 war protestors, but instead was protesting the art world. His paintings had stood out as stylistically distinctive, and he was anxious to make an impact—not only by developing a new approach to painting but by developing an entirely new philosophical approach to teaching art. He became certain that the development of his own unique style would only find maturity in a climate insulated from the successive waves of -isms that were sweeping across the country and, he felt, leaving in its wake a cacophony of styles.

Taylor successfully convinced the Tyler School that he could fulfill the obligations of his master’s thesis abroad. Having long been inspired by Greek mythology, Henry Miller’s travelogue, The Colossus of Maroussi, and the sensuous nineteenth-century Romanticism of the poet-painter e. e. cummings’s work Xaipe, he was determined to find an idyllic environment on one of the islands in the Cyclades group of the Aegean Sea. He quickly married his undergraduate girlfriend and hopped a Yugoslav freighter to Naples, Italy.

After exploring the many islands of the Aegean via ferries, by March 1966 they settled on the unspoiled small island of Paros, at the center of the Cyclades. The island’s culture and unique environment provided a blank canvas conducive to forging a new life in art. It was as good as undiscovered. There were perhaps a dozen foreigners living on the island among its population of less than two thousand, and the people stood out as the friendliest of any island they had explored. Bicycles were the mode of transportation because there were only two cars. Anything heavy required donkeys pulling carts. There were no telephones, no television, and no U.S. radio or newspapers. That also made Paros largely insulated from contemporary art movements.

For Taylor, just turning twenty-three, it was the perfect place to officially open the first art school in the Aegean in June of 1966—the Aegean School of Fine Art—still active today. Everyone who knew him—classmates, colleagues, faculty, and students—consistently cited his charisma as a powerful catalyst for his mission of creating a then new cross-disciplinary approach to art education. His notoriety as an out-of-the box teacher would continue to attract more international students.

The tragic ending to this story is that Taylor regularly predicted with accuracy his dénouement—that he would not reach forty. He left behind a uniquely exhilarating body of work, legions of students, and the distinction of being the only American expatriate artist to have lived permanently in the Aegean.