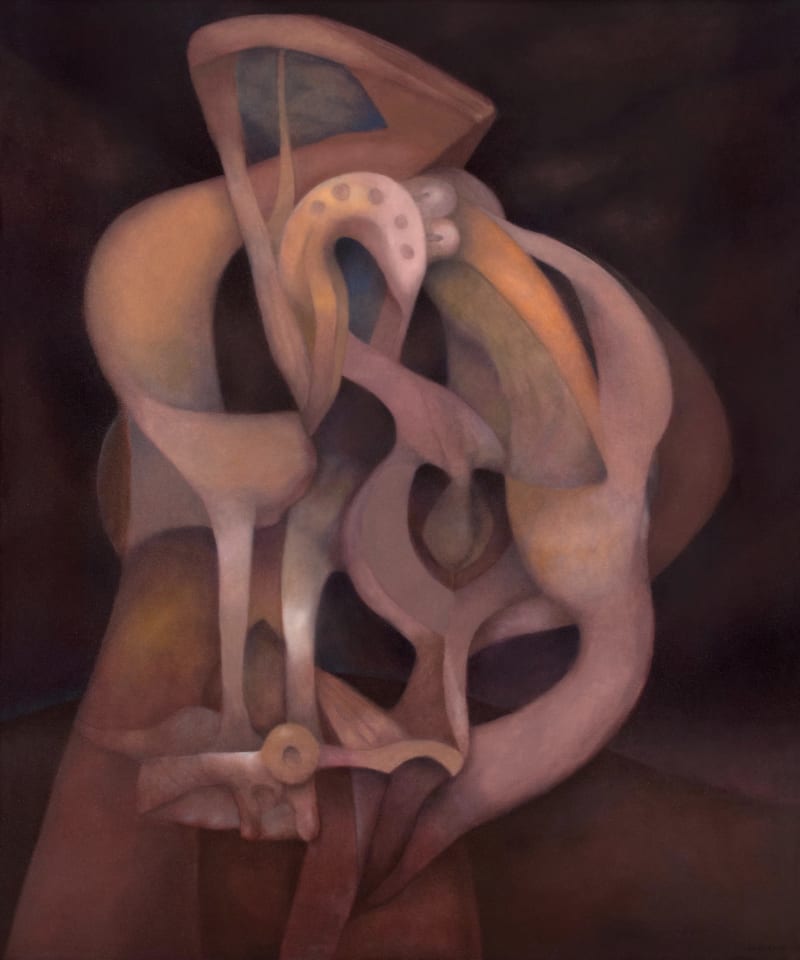

Soriano moved away from a mystification of geometric forms and toward a conception of the unconscious as a realm where spirit, dream, simultaneity and ecstasy are vibrant and immediate realities.

One of the major Latin American artists of his generation, Rafael Soriano (1920-2015) became known for his evocative paintings that foreground light as subject matter. He was a key figure in introducing Concrete Art, a geometric style devoid of symbolism or representation, in Cuba. In the 1950s, Soriano created works with post-Mondrian, rectilinear compositions and bold, flat colors. Along with painters José Mijares, Sandu Darie, Lola Soldevilla, Luis Martinez Pedro and others, Soriano was a member of the group Los Diez Pintores Concretos (Ten Concrete Painters), which advocated for a utopian form of art as realized through concrete and geometric abstraction. In the wake of the 1959 revolution and Fidel Castro’s regime, however, Soriano fled to Miami in 1962 with his wife Milagros and young daughter Hortensia, leaving behind a thriving artistic career in Cuba. Working as a graphic designer and occasional teacher in Miami, Soriano stopped painting for two years out of exiled despair. Upon receiving a spiritual revelation in a dream, Soriano began painting again and his style transformed from geometric abstraction into the oneiric, luminous gradations of light and shadow he came to be known for. In a 1997 interview, he stated, “The anxieties and sadness of exile brought in me an awakening. I began to search for something else; it was through my painting. . . And I went from geometric painting to a painting that is spiritual. I believe in God, I believe in the spirit.” (1)

This profound shift in Soriano’s work from Constructivism to Surrealism was underway by the late 1960s. As art critic and poet Ricardo Pau-Llosa noted, “In Soriano’s case, the leap was from one kind of ‘purity’ to another, from the court of Pythagoras. . . a Cartesian purity. . . to that of Turner, Jung, El Greco, and Goethe. . . Soriano moved away from a mystification of geometric forms and toward a conception of the unconscious as a realm where spirit, dream, simultaneity and ecstasy are vibrant and immediate realities.” (2) Indeed, Soriano himself described his mature works as “a dialogue between Constructivism and Surrealism, in which I seek the transcendental purity of the first and the sensuous intensity of the second.” From the late 1960s into the 1990s, Soriano developed a rich visual vocabulary, one filled with nocturnal forms that seem to bloom and metamorphize during the night. Recalling at times diaphanous curtains or sinewy muscles, these mysterious forms are all allusion and association, evading attempts at representational capture. Soriano’s paintings from this mature period are revelations of some hidden dimension that cannot be possessed, bringing to mind Paul Klee’s statement that “art plays an unknowing game with ultimate things.” As the poet Juana Rosa Pita observed, “Soriano does not see objects but rather reminiscences, magnetism, incantations, harmony, and presence.”

Like his counterparts in other Latin American artists like the Chilean painter Roberto Matta, who was also interested in the aesthetics of metaphysical forms, Soriano sought to evoke both flesh and spirit in his paintings. (3) What set apart Soriano’s work, however, was its ability to make light an identifiable, felt substance, a worthy subject matter on its own rather than a compositional technique or tool. His paintings are about the “life-giving power of light, where furrows define shapes by touching a border, caressing a surface or penetrating spaces.” (4) Seeking to dwell in a realm where, according to the artist, “the intimate and the cosmic converge,” his paintings recall Emerson’s notion of the soul in his well-known essay The Over-Soul: “The soul is not… a function, like the power of memory… [nor] a faculty, but a light. . . an immensity not possessed and cannot be possessed.”

Born in 1920 in the Matanzas town of Cidra, Soriano decided at a young age to become a painter. At the age of sixteen, he attended Havana’s San Alejandro School of Art, where seven years later, in 1943, he graduated as Professor of Painting, Drawing, and Sculpture. During his studies, he became close friends with avant-garde artists Fidelio Ponce and Victor Manuel. After his time at San Alejandro, Soriano returned to Matanzas where he helped found the School of Fine Arts of Matanzas, where he was a teacher and director until his exile in 1962. Upon resettling in Miami, he worked as a graphic artist and an occasional instructor at Miami’s Catholic Welfare Bureau (1963-1965) and later at the University of Miami’s Cuban Cultural Program (1967-1970), painting tirelessly at night. Soriano’s work is held in the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C.; Blanton Museum of Art, Austin; Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University; Lowe Art Museum, Miami; Denver Art Museum; Cuban Museum of Arts and Culture, Miami; Museo de Arte Zea, Medellin, Colombia; Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de La Habana, Cuba; Pérez Art Museum, Miami; McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College; among others.

- Juan Martinez, Oral History Interview with Rafael Soriano, December 6, 1997. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institute.

- Ricardo Pau-Llosa, Rafael Soriano and The Poetics of Light (Editorial Concepts, Inc., 1998), p. 9.

- Pau-Llosa, p. 8.

- Alejandro Anreus, “Rafael Soriano: A Painter’s Painter,” in Rafael Soriano: Other Worlds Within: A Sixty Year Retrospective (Lowe Art Museum, 2011), p. 13.

Works