Hood described her work as juxtapositions of colors set “against one another” and as “landscapes of my psyche.”

Dorothy Hood (1918-2000) was a brilliant, innovative figure in American modernism and one of Texas’s most celebrated artists. Best known for her large-scale transcendent canvases, Hood fused Abstract Expressionism with elements of Modernism and Surrealism. She described her work as juxtapositions of colors set “against one another” and as “landscapes of my psyche.”

Raised in Houston, Hood studied at the Rhode Island School of Design on a full scholarship before moving to New York City, where she worked as a model to fund her studies at the Art Students’ League. In 1941, on what was intended to be a two-week painting trip, Hood drove to Mexico City with two friends. Enthralled with the zeitgeist of Mexico, she remained in Mexico City and Puebla for more than twenty years, encouraged by the greater level of freedom for women artists. She found herself at the forefront of Mexico City’s vibrant avant-garde community that included a dynamic mix of exiled European intellectuals and Mexican artists such as Frida Kahlo, Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, Sophie Treadwell, Luis Buñuel, and Pablo Neruda. Hood found immediate support among the creative community, including the renowned muralist José Clemente Orozco who mentored her from 1943 to 1960. Reflecting on her time in Mexico, Hood observed, “The Mexican Revolution was only twenty years over—its fires and illusions and memories were still alive in the air. It was an era of action for artists and intellectuals.” (1)

Dorothy Hood (1918-2000) was a brilliant, innovative figure in American modernism and one of Texas’s most celebrated artists. Best known for her large-scale transcendent canvases, Hood fused Abstract Expressionism with elements of Modernism and Surrealism. She described her work as juxtapositions of colors set “against one another” and as “landscapes of my psyche.”

Raised in Houston, Hood studied at the Rhode Island School of Design on a full scholarship before moving to New York City, where she worked as a model to fund her studies at the Art Students’ League. In 1941, on what was intended to be a two-week painting trip, Hood drove to Mexico City with two friends. Enthralled with the zeitgeist of Mexico, she remained in Mexico City and Puebla for more than twenty years, encouraged by the greater level of freedom for women artists. She found herself at the forefront of Mexico City’s vibrant avant-garde community that included a dynamic mix of exiled European intellectuals and Mexican artists such as Frida Kahlo, Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, Sophie Treadwell, Luis Buñuel, and Pablo Neruda. Hood found immediate support among the creative community, including the renowned muralist José Clemente Orozco who mentored her from 1943 to 1960. Reflecting on her time in Mexico, Hood observed, “The Mexican Revolution was only twenty years over—its fires and illusions and memories were still alive in the air. It was an era of action for artists and intellectuals.” (1)

Hood’s first exhibition took place in Mexico City at the GAMA Gallery in 1943, featuring realist portraits of animals and children. Early on, her close friend, the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, wrote about Hood’s work: "There is in the painting of Dorothy Hood a desperate interrogation, an aesthetic of human pain.” She participated in group shows at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1945 and 1947, and held her first New York solo exhibition at the Willard Gallery in 1950. In the 1950s, Hood’s style evolved into abstract expanses of color which she termed “abstract surrealism.” During this period, she and her husband, the Bolivian conductor and composer José Maria Velasco Maidana, whom she married in 1946, frequently traveled to New York City. In 1957, Art in America named Hood as one of the year’s “new talents” on the recommendation of MoMA curator Dorothy Miller.

These “landscapes of my psyche,” as she often described her paintings, explore the fracturing of imagined and emotional landscapes. A great painting, she stated, “makes you remember something out of time.” Always careful to maintain her artistic independence, Hood nonetheless voraciously metabolized a wide range of sources. (2) Influenced by the theories of Jung and Freud, Hood also read widely on topics of mythology, science, and space exploration. Artists whose work had great impact on her practice included Georgia O’Keeffe, Max Ernst, Arshile Gorky, Constantin Brancusi, James Ensor, and Henri Matisse.

Art historian Robert Hobbs has written of Hood that “she certainly is one of the most important artists from that generation. . . She represents not only Texas but great connections with Mexico and New York, because she was carrying on artist conversations in a number of different worlds. She’s not only regional, she’s also national and international.”

In the early 1960s Hood left Mexico, returning to Houston with her husband, whose health was declining. In Houston, she found freedom and ambition in making large-scale paintings in her mature, elegiac style. Hood combined sweeping fields of color fractured by jagged fissures and probing color. These works quickly placed Hood among the notable abstract painters of her generation. In spite of the male-dominated art world of Houston, Hood established herself as a force through three solo exhibitions in major Texas museums by 1971: Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston, Sewell Art Gallery at Rice University, and Witte Memorial Museum in San Antonio. Despite the enthusiastic support of noted American critics, curators, and philanthropists like Clement Greenberg, Barbara Rose, Dorothy Miller, and Dominique de Menil, Hood’s intentional distance from New York dampened her growing recognition. (3) (“If she had been in New York, it would have been a whole different story,” said the critic Barbara Rose. “I think the paintings are first-rate.”)

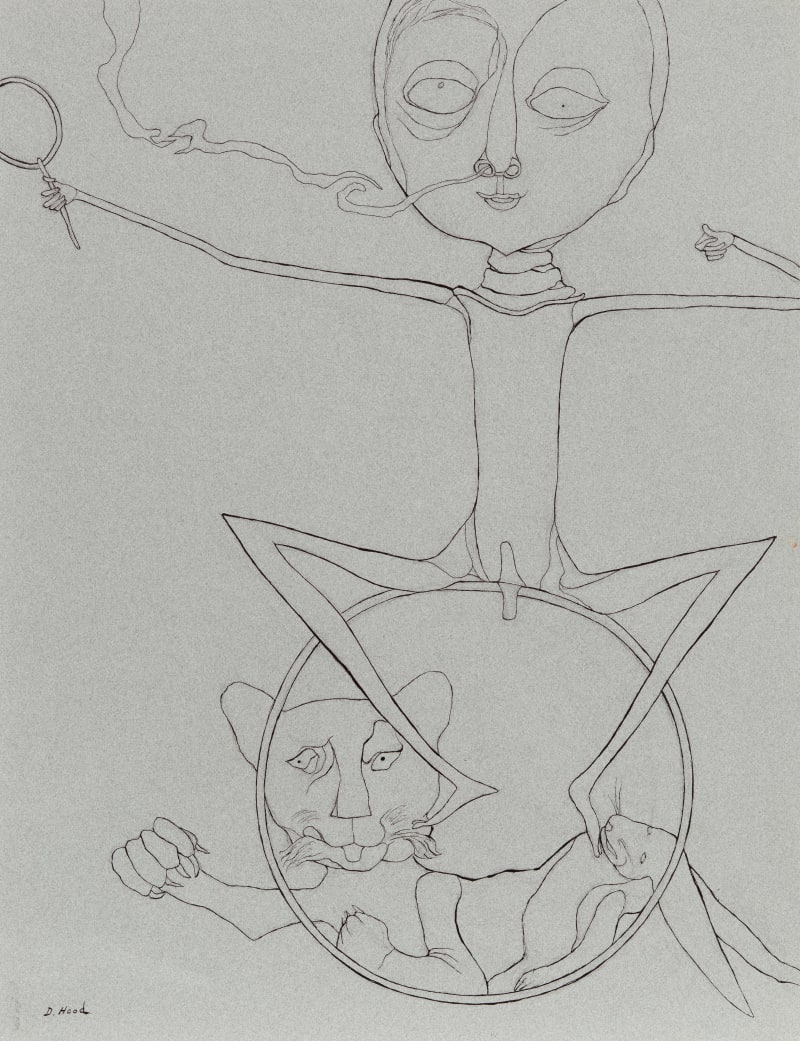

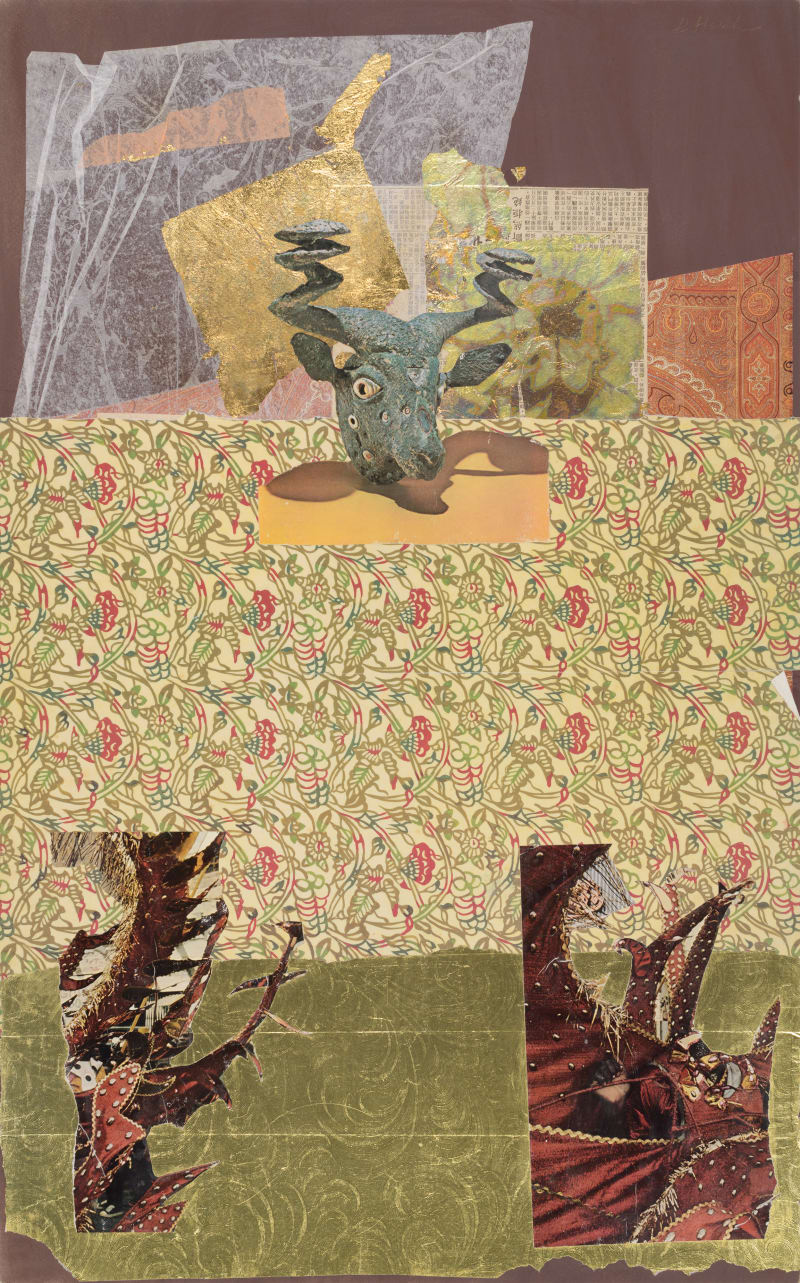

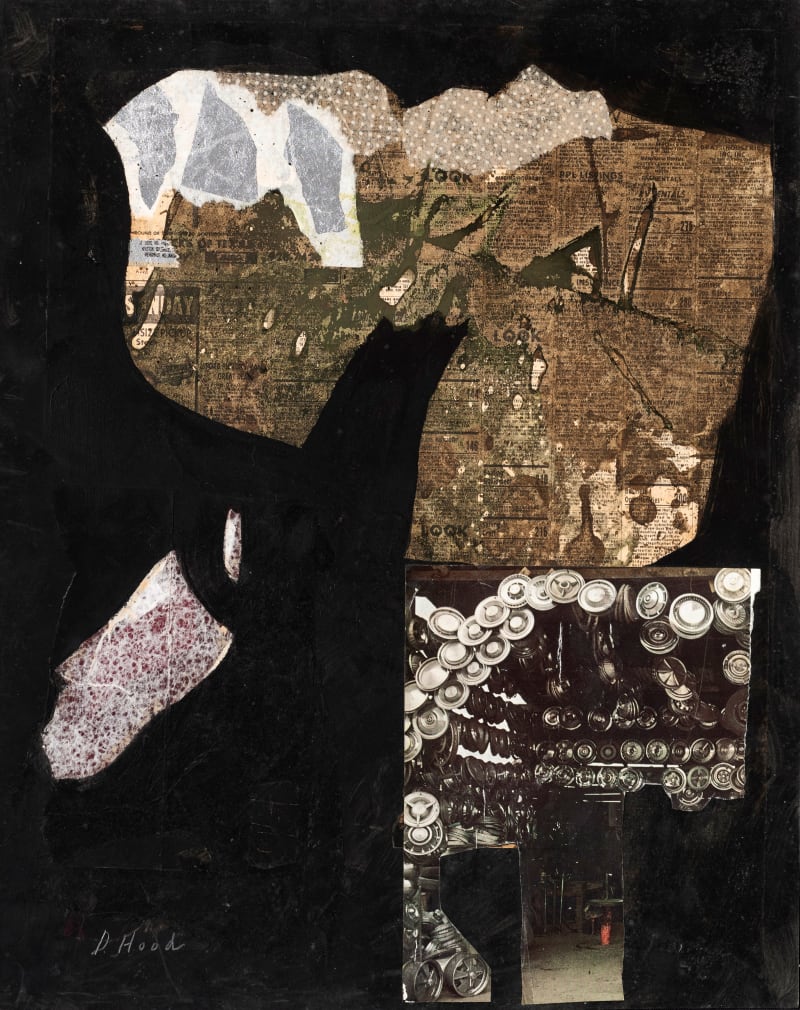

In 1980, for an essay in Art Journal, Hood articulated the importance of the concept of the void in her art and its role as an impetus for creation. “The psyche, that mute, measuring relative of the void, is forever active and creating,” she wrote. The void is “saying the most by the simplest means,” and is beyond mythology, religion, sociology, or politics. (4) During this period, Hood also spent time at NASA, forming relationships with scientists and astronauts to create a series of drawings about the inner and outer cosmos. "I was sketching outer space before NASA started," the artist once stated. In the 1980s, Hood also began experimenting with collage using materials such as stationery, newspaper clippings, textile scraps, gold leaf, and gift wrap. Many of her collages from this time play with multi-dimensions and imagery related to the space age and cybernetics.

Born in Bryan, Texas, Dorothy Hood took refuge in artmaking from a young age, growing up as a child of a banker father who was often away and a mother who struggled with mental illness. “Since I was a child,” Hood explained, “I have known what I was going to do [and] it became more and more of a necessity as time went on.” (5) Alongside her artistic practice, Hood also taught at the school of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston from 1963 to 1972. The artist passed away in 2000 after battling breast cancer.

In 2016, the Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christi mounted the first major retrospective of Hood’s work, featuring 160 paintings, collages, and works on paper. In 2018, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston presented an exhibition titled Kindred Spirits: Louise Nevelson & Dorothy Hood. Hood’s work is included in numerous collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art; Philadelphia Museum of Art; the Menil Collection; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Brooklyn Museum, New York; Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, NY; Ogden Museum of Southern Art; Dallas Museum of Art; Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, Texas; San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art; among others.

- Quoted in Katy Vine, “Fame in the Abstract,” Texas Monthly, September 2016.

- Sylvia Moore, “Dorothy Hood Interviewed,” Women Artist News, November 1978.

- “Dorothy Hood: Illuminated Earth,” exhibition catalogue. Houston, Texas: McClain Gallery, 2019.

- Dorothy Hood, “Sighting the Invisible Frontiers,” Art Journal, vol. 39, no. 4, summer 1980.

- Moore, “Dorothy Hood Interviewed.”