The poetic quality of his work is rooted in his mastery of the technical aspects of painting.

As a painter, William Baziotes regularly drew on Surrealist and primitive sources. The poetic quality of his work is rooted in his mastery of the technical aspects of painting, his ability to mine the cultures of the past, and, most importantly, his talent for marrying the cerebral and whimsical. Writings by Charles Baudelaire and the French Symbolist poets provided potent inspiration for Baziotes, who also yearned to express deep-seated emotions and states of mind.

As a painter, William Baziotes regularly drew on Surrealist and primitive sources. The poetic quality of his work is rooted in his mastery of the technical aspects of painting, his ability to mine the cultures of the past, and, most importantly, his talent for marrying the cerebral and whimsical. Writings by Charles Baudelaire and the French Symbolist poets provided potent inspiration for Baziotes, who also yearned to express deep-seated emotions and states of mind.

Baziotes adopted the Surrealists’ investment in fantasy and the principle of automatism as points of departure for his compositions. In 1942, Baziotes, his wife Ethel, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and Lee Krasner began to meet regularly to play Surrealist games and to write poetry together. This spirit of openness and collaboration shaped Baziotes’ artistic sensibilities and hastened the incorporation of Surrealist elements in his work. In order to balance the spontaneity of automatic painting, Baziotes also assimilated Synthetic Cubist techniques; he was familiar with the work of Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso.

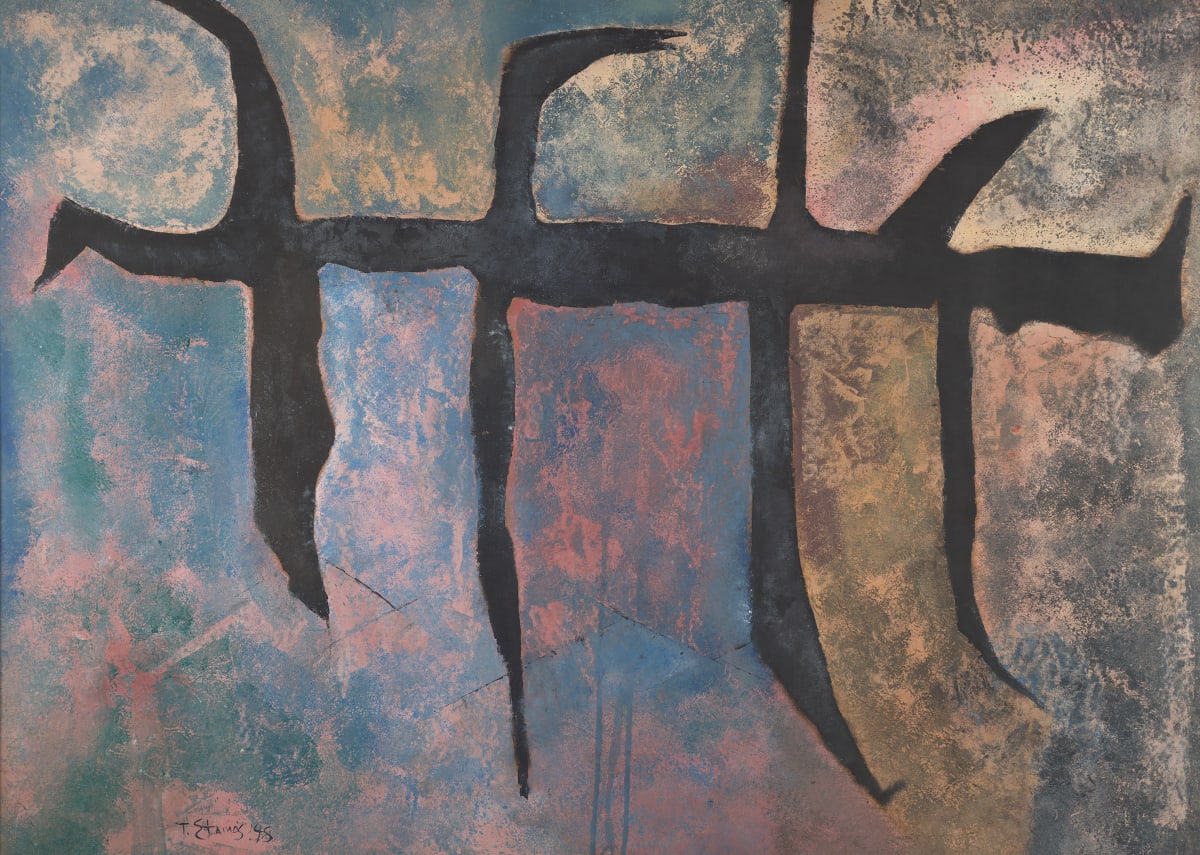

Baziotes’ understanding of Surrealism was highly personal—he drew inspiration from myriad sources and used many layers of translucent glaze to create psychically charged paintings that resonated with the memory of their creation. Although spiritual intensity suffuses the work, the iconography, usually biomorphic, is abstracted and evocative, never explicit. Baziotes explained this intentional ambiguity in 1959: “It is the mysterious that I love in my painting. It is the stillness and the silence. I want my picture to take effect very slowly, to obsess and to haunt.”(1) Rarely literal, his titles are clues to the layers of symbolic and personal meaning.

Born and raised in Pittsburgh, Baziotes began his formal art training in 1933 at the National Academy of Design in New York City, where he studied through 1936 with Charles Curran, Ivan Olinsky, Gifford Beal, and Leon Kroll. After three years at the Academy, Baziotes started painting realistic landscapes and still lifes. While employed by the WPA Art Project in the late 1930s, he began to execute works in a more stylized manner and showed diminishing interest in rendering subjects with anatomical verity.

The 1940s brought close relationships with many artists in the emerging Abstract Expressionist group. Although Baziotes shared their interest in primitive art and automatism, his work consistently displayed stronger affinities with European surrealism. Baziotes met Chilean-born Surrealist Roberto Matta in May 1940, the same year he exhibited with the Surrealists in a group show organized for the New School. By 1941, Baziotes was actively experimenting with abstraction and Matta introduced him to Robert Motherwell. The following year Baziotes exhibited in the “First Papers of Surrealism” exhibition, along with artists including Motherwell and David Hare. Baziotes was honored with his first one-man show in New York in 1944 at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century Gallery. His next solo showing was in 1946 at the Kootz Gallery, which represented Baziotes through 1958. In 1962, he was one of the celebrated artists included in Sydney Janis’ important exhibition, Ten American Painters.

Baziotes, who was of Greek descent, often used the forms that appeared in the ancient sculpture he owned, and during the 1950s he studied Greek sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Baziotes drew visual inspiration from a wide range of sources, including the rich colors of Persian miniatures and even the grotesque variations seen in specimens from the natural sciences.

In the latter part of his career, Baziotes taught extensively. He became a founding member of the school on Eighth Street in 1948 and in the years that followed, he taught at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, People’s Art Center, the Museum of Modern Art, and Hunter College in New York.

1) William Baziotes, It Is 4 (Autumn 1959), 11.