Rivers’ oeuvre shows his willingness to explore new styles, techniques, and media

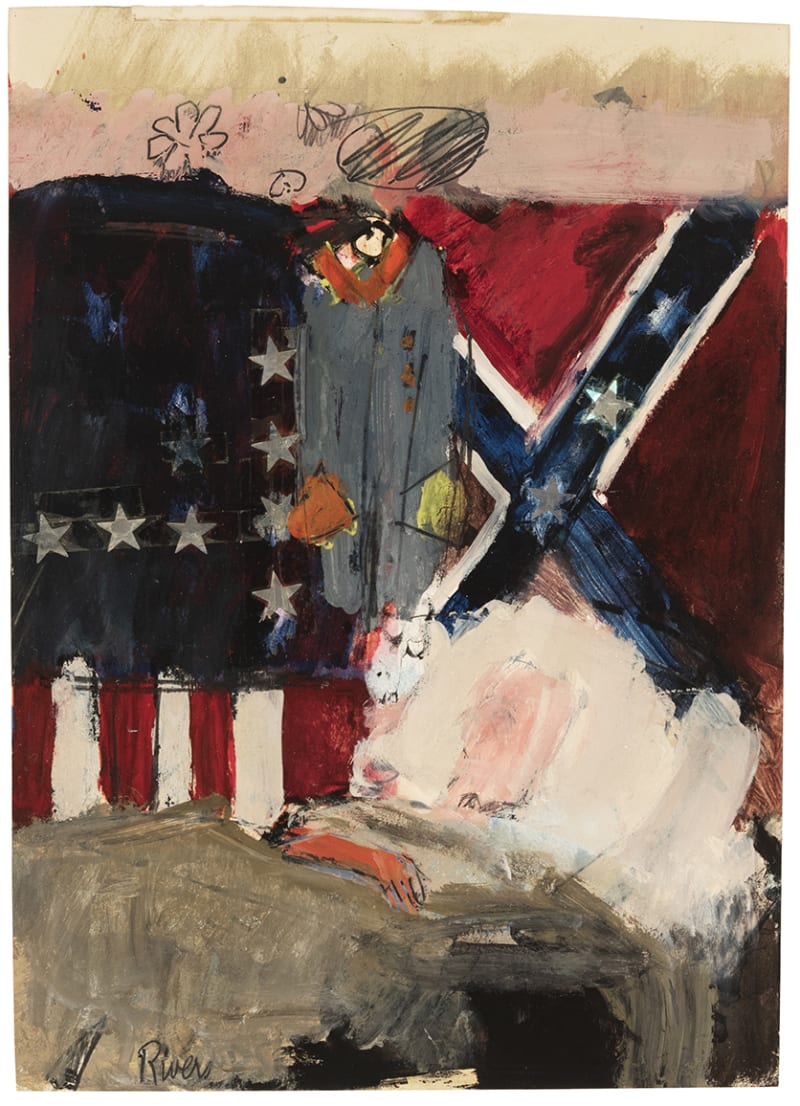

An artist, jazz musician, former quiz show participant, part-time Hamptons resident, and flamboyant gadabout, Larry Rivers’ celebrity persona sometimes overshadows the depth and range of his artwork. Spanning seven decades and a variety of media, Rivers’ oeuvre shows his willingness to explore new styles, techniques, and media, and also reveals his commitment to signature elements throughout his work: a technical virtuosity, repeated art historical allusions, references to popular culture, clever wit, and a sustained engagement with familiar, intimate subjects.

An artist, jazz musician, former quiz show participant, part-time Hamptons resident, and flamboyant gadabout, Larry Rivers’ celebrity persona sometimes overshadows the depth and range of his artwork. Spanning seven decades and a variety of media, Rivers’ oeuvre shows his willingness to explore new styles, techniques, and media, and also reveals his commitment to signature elements throughout his work: a technical virtuosity, repeated art historical allusions, references to popular culture, clever wit, and a sustained engagement with familiar, intimate subjects.

For Rivers, the 1950s were a decade of portraits and interiors, and during this period, he gained a deserved reputation as America’s most gifted young portraitist. He had studied with Hans Hofmann in 1947 and 1948, where he learned Hofmann’s theories of expressive color, and by 1950 he was associating with the circle of artists who became known as the core of the Abstract Expressionist movement.

His first of twelve solo shows at Tibor de Nagy gallery was held in December 1951; reviewing the exhibition for the Nation, critic (and painter) Manny Farber described Rivers’ work as “bleeding with ‘compassion’ and bursting with bravura”.(1) Broad areas of bold, all-over brushwork characterize portraits of this period, conflating background and figures. A review of work in a show the following year observed that “paint areas are organized into masses that move intensely and passionately into one another.”(2) In the next few years, Rivers would use this idiom to court controversy with paintings such as Washington Crossing the Delaware, an irreverent riff on Emmanuel Leutze’s masterpiece, and his 1955 double portrait of his nude mother-in-law (Double Portrait of Berdie).

In the 1960s, Rivers invested his works with the markings of popular culture—the detritus of modern life and everyday consumerism. However, amid the stenciled brandings of Lucky Strike and Dutch Masters were the luscious brushstrokes and colorful passages of his 1950s period, stylistic hallmarks that were to remain with Rivers for the rest of his career. The scholar Helen Harrison assesses the renewed significance of Rivers’ work in her preface to a retrospective exhibition in 1984, “… a great many of Rivers’ canvases of the 1950s and 1960s look remarkably fresh and vital in the context of today’s paintings.” Other scholars, collectors, and museum curators have concurred with Harrison—Rivers’ works are represented in the collections of almost every major museum in the United States and Europe.

Notes:

1) Manny Farber, “Art,” The Nation (October 13, 1951).

2) Robert Goodnough, ARTnews 52, 8 (December 1952), 44. Quoted in Barbara Rose, “Larry Rivers: Painter of Modern Life,” in Larry Rivers: Art and the Artist (Washington: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 2002), 27