The works offer a keyhole aesthetic into hidden desires, forgotten dreams, or personal obsessions.

Since the first-quarter of the twentieth-century, box construction has become a unique expressive device for many artists, as exemplified by the varied approaches of Joseph Cornell, Pierre Roy, Leo Rabkin, Lucas Samaras, Maureen McCabe, Elspeth Halvorsen, and Ted Victoria, seven artists featured in our upcoming exhibition “Image in the Box: Cornell to Contemporary,” November 20, 2008- January 10, 2009. Comprised of 59 works covering the period from the 1920s to the present, the assemblage of box constructions presented evokes magical journeys of the imagination, captures the poetry within the most unassuming everyday objects, and conjures the mysterious, the playful, the beautiful, and sometimes, the dangerous. The works offer a keyhole aesthetic into hidden desires, forgotten dreams, or personal obsessions. At the same time, many also present motifs rooted to the particular sites, historical events, and aspects of popular culture that define the realities of twentieth-century life.

Since the first-quarter of the twentieth-century, box construction has become a unique expressive device for many artists, as exemplified by the varied approaches of Joseph Cornell, Pierre Roy, Leo Rabkin, Lucas Samaras, Maureen McCabe, Elspeth Halvorsen, and Ted Victoria, seven artists featured in our upcoming exhibition “Image in the Box: Cornell to Contemporary,” November 20, 2008- January 10, 2009. Comprised of 59 works covering the period from the 1920s to the present, the assemblage of box constructions presented evokes magical journeys of the imagination, captures the poetry within the most unassuming everyday objects, and conjures the mysterious, the playful, the beautiful, and sometimes, the dangerous. The works offer a keyhole aesthetic into hidden desires, forgotten dreams, or personal obsessions. At the same time, many also present motifs rooted to the particular sites, historical events, and aspects of popular culture that define the realities of twentieth-century life.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with essays by scholars Jeffrey Wechsler and Townsend Ludington. Wechsler is Senior Curator at the Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University. Among his many accomplishments are the exhibits Asian Traditions/ Modern Expressions: Asian American Artists and Abstraction, 1945-1970 (1997), Abstract Expressionism: Other Dimensions (1989), and the groundbreaking Surrealism and American Art, 1931-1947 (1976). Dr. Townsend Ludington is Distinguished Professor Emeritus of American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Ludington is the author of the acclaimed biographies Marsden Hartley: The Biography of an American Artist and John Dos Passos: A Twentieth-Century Odyssey.

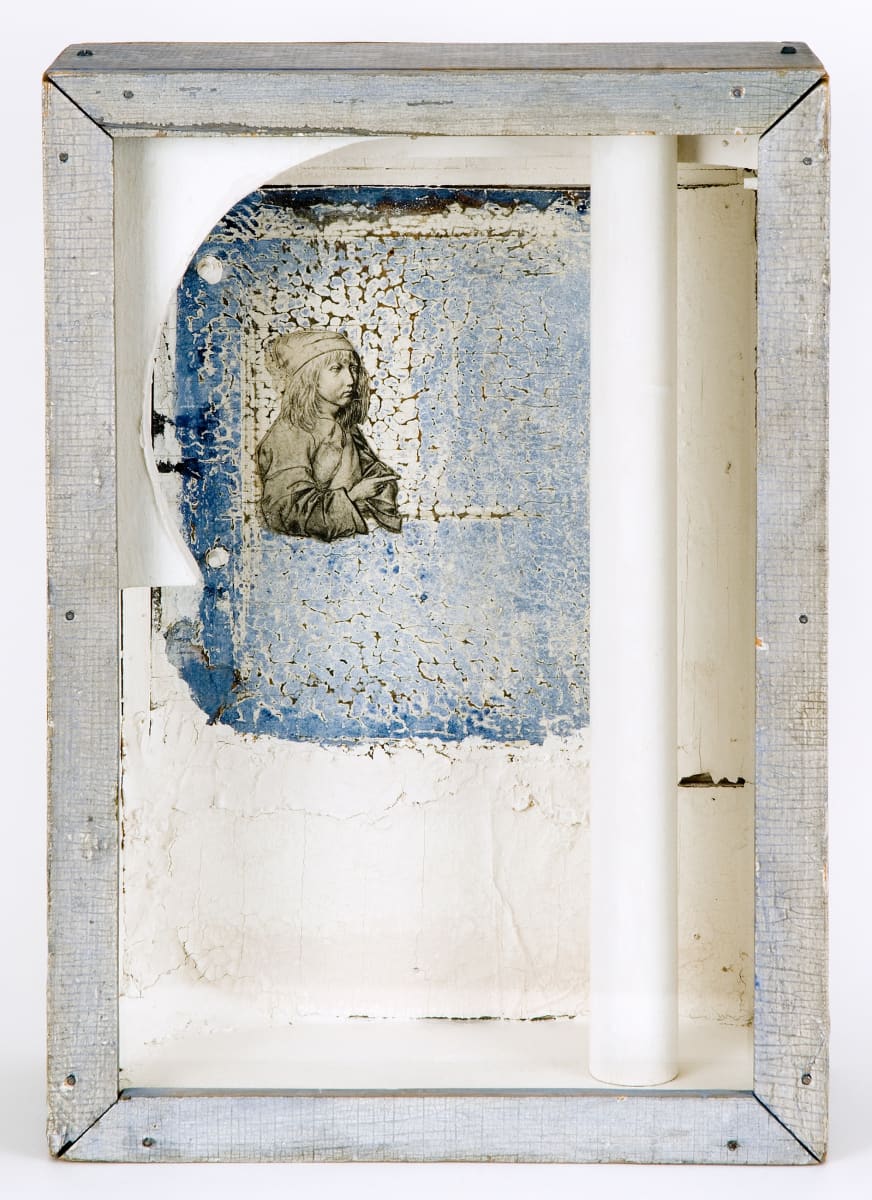

Joseph Cornell (1903-1972) is inextricably linked with box construction and often considered the pioneer of the medium. Developing his practice of collage and assemblage in the mid-thirties, Cornell emerged from the influential New York Surrealist circle. Establishing his iconic style, he continued to produce boxes and collages throughout his career. As the works Untitled (Dürer), c. 1952 and Constellation Variant, 1955-58 suggest, Cornell was a master at establishing understated but vital connections between found objects. Images of celestial forms and Renaissance art suggest voyages of time and place, hinting at the fragility and endless possibilities of experience. Cornell’s art would impact many American artists from the Abstract Expressionist circle to the contemporary artists featured in this exhibition.

Cornell’s imagery has a unique artistic kinship with the Magic Realist painting of the French artist Pierre Roy (1880-1950). “Image in the Box” examines the powerful visual associations between Roy’s and Cornell’s work, a subject that has received little attention within Cornell scholarship, with the exception of the groundbreaking research undertaken by Jeffrey Wechsler, who presented the lecture “A Source for the Imagery of Joseph Cornell” at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in 1978. Highlighted in this exhibition, his analysis of the two artists reveals a considerable amount of shared imagery. Roy’s motifs include the butterfly featured in Papillon, 1933, as well as wineglasses, hanging weights, sand, shells, eggs, scientific charts, pins, paper flags, and ceramic statuettes arranged in compositions strikingly similar to Cornell’s. In Roy’s Pêcherie de Cétacés, 1926, the artist paints an open rear wall into his boxes, a technique Cornell echoed by placing photographs or astronomical imagery at the back of his boxes.

Contemporary artists have long been attracted to the flexibility of the box medium, finding it allowed them a unique format in which to incorporate many technical, material, and philosophical points of view. A student of William Baziotes and Hale Woodruff, Leo Rabkin (b. 1919) has been making boxes since the 1950s, with a particular attention to the viewer’s intimate interaction with the material. An avid collector of folk art and the former president of the American Abstract Artist group, he was an early contributor to the development of conceptual art, in which meaning lies with viewer experience rather than the rarified art object. In Fabrics for Mending, 1970s, fluffy dandelion seeds float within a wooden box and their soft, tender quality highlights the delicacy of the natural world. The materials in Habanello, c. 1991 appear equally surprising, with the contrasting textures of metal and stone appealing to the senses.

In contrast to Rabkin, Samaras’ renowned artistic personality is a purposefully chimerical one, leading to his use of a range of media including painting, sculpture, drawing, and photography. Samaras’ boxes were crucial components of his early career, gaining him great notoriety since the 1960s, with production continuing into the 1980s. Samaras (b. 1936) used the box as part of his self-centric presentations, frequently including photographic self-portraits, such as in Box # 101, 1977-89. Earlier works in the Chicken Wire series, such as Untitled, 1965 employ simplified shapes, referencing in part the Minimalist trends of the period.

Far removed from Samaras’ aesthetic, Elspeth Halvorsen (b. 1929) employs organic forms including tree branches, eggs, and the female torso, creating an atmosphere of deliberation and calm in her box constructions. These elements, also components in Cornell’s work, combine to suggest mysterious and personal narratives, such as the sense of an event unfolding created in Fairy Tale: Rescue, 2003. Halvorsen studied at the New School for Social Research and the Art Students League and in 1955 moved to Provincetown, Massachusetts, with her late husband, the artist Tony Vevers. Her work is deeply connected to her surroundings, to the ocean, and to the natural cycles of birth and rebirth as embodied in Robin’s Egg, 2005.

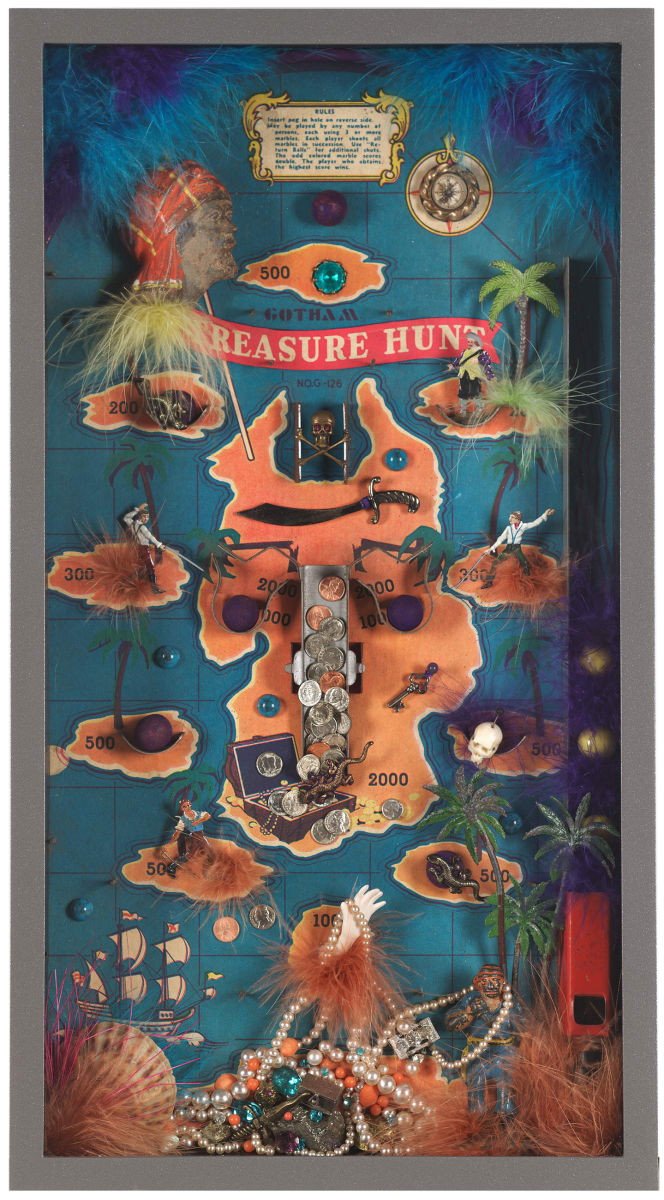

Whereas Halvorsen frequently plumbs the potential of the reductive image, Maureen McCabe (b. 1947) often creates intricate works in which many elements compete for the viewer’s attention. A professor of art at Connecticut College, McCabe began working in collage as a student at the Cranbrook Academy of Art. Her densely arranged symbols in Ionia, 2007 and Star-Light, 2007 explore themes of magic, mythology, tragedy, and wit. The carefully researched themes are documented on the verso of her works with notes, articles, and images from popular culture. McCabe’s constructions are far from random collections. Her approach to the selection of imagery is thoroughly researched, calculated, and elaborately orchestrated.

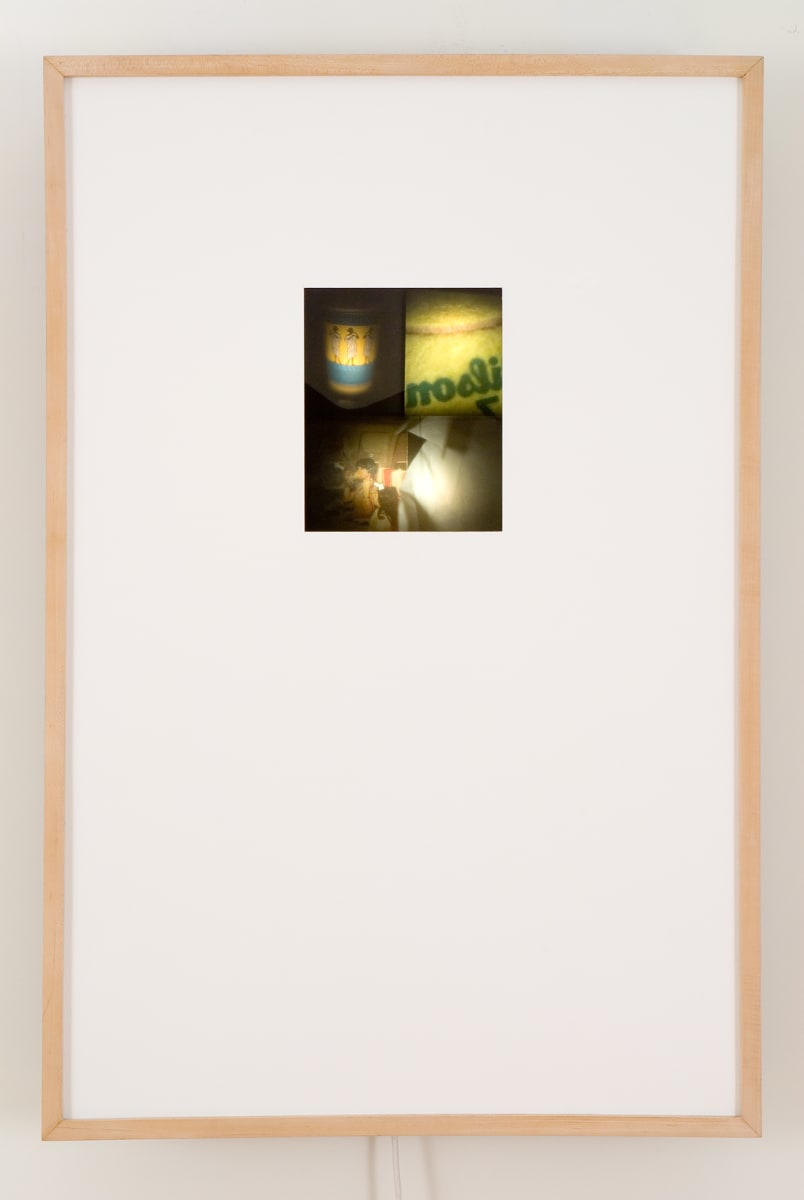

Ted Victoria (b. 1944) further extends the stylistic and technical possibilities of box imagery by his inclusion of projected and moving images. Victoria began his avant-garde experimentation with projected images in the 1960s and 1970s, after being exposed to Pop art, the assemblages of Robert Rauschenberg, and Cornell’s films. His construction incorporates technology, including low-tech tools—lenses, clockwork mechanisms, light bulbs, and the use of the camera obscura—in order to project images of actual objects. These include a miniature chair in The Magic Chair, 2008 and a ring, miniature tire, and cigarette lighter in Evidence, 1992-93. Thus, the artist’s works epitomize the notion of “the image in the box.”

The artists included in the exhibition respond to events both personal and cultural, finding their answers in objects and images. To express their ideas they delve into personal hordes, retrieve items from drawers, and dig into piles of miscellanea that fill shelves, storage bins, or even whole rooms. Objects are sought out, or purchased, or discovered at random, but assume their most significant meanings within a box.